Clare Boothe Luce, with only a tinge of hyperbole, referred to the 1965 version of New York City as “the biggest urban mess on earth.”1 In that same year, the American conservative movement’s condition could not have been considered much better. The Republican Party’s right-wing presidential candidate had just suffered a defeat of stunning magnitude, its northeastern liberal wing was in rebellion, and the party’s governing philosophy was up for grabs. With Barry Goldwater routed, the center of gravity in the Republican Party was moving sharply left and toward the East; the two men vying for the party’s leadership, Richard Nixon and Nelson Rockefeller, lived in the same Manhattan apartment building separated by a mere six floors.

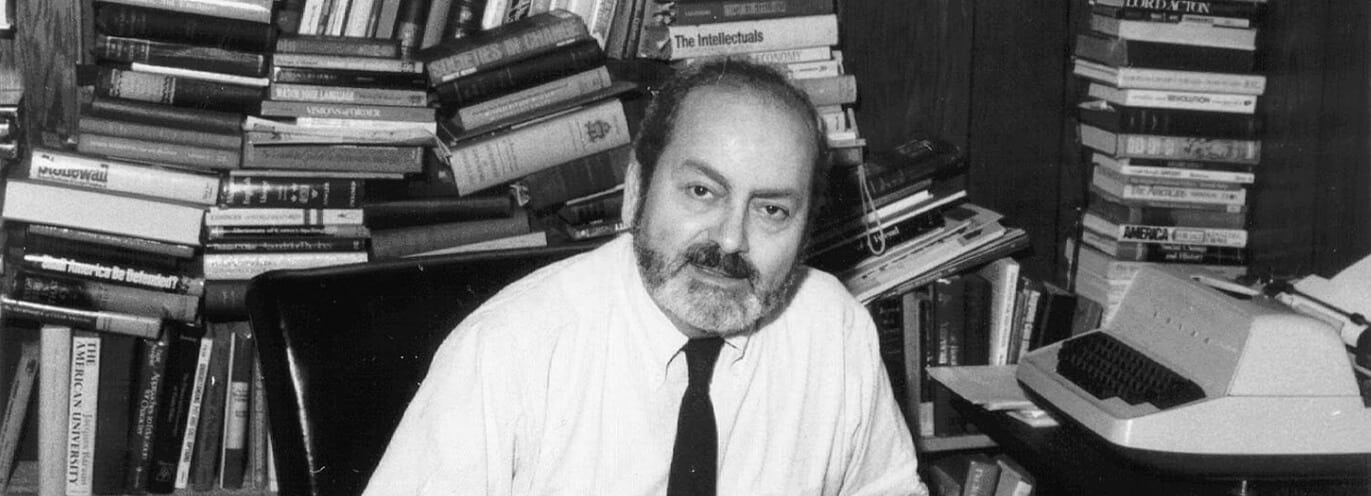

In the spring of 1965, the plight of the Republican Party weighed heavily on William F. Buckley Jr.’s mind. At the time, the thirty-nine-year-old Buckley was spending some weekdays in his Park Avenue apartment, commuting to the midtown National Review offices by day and jousting with New York’s highbrow society by night.

The city outside his part-time residence was in full-scale decline. The crime rate was high, deficits higher; a drought had made water scarce; traffic was slow; municipal employee strikes were prevalent; the previous summer’s race riots in Harlem were fresh in people’s minds. Over the past decade, nearly a million members of the white middle class had left the city.

“You and I are not in fact running for mayor,” Buckley wrote in his syndicated column in late May. “But suppose we were?”2 He outlined, “half in fun,” a ten-point plan for conservative governance of New York City. A few days later, as National Review prepared to reprint the column, Buckley’s sister Priscilla proposed a playful cover banner: “Buckley for Mayor.”

The line was a joke, but in the first week of June, Buckley later noted, “the idea came to me very suddenly”: why not actually run for mayor as the candidate of the state Conservative Party?3 With little forethought, and no groundswell of popular support, Buckley committed to the race and was enthusiastically backed by the Conservative hierarchy.4

Although his brother James later remarked, “Bill did get into the thing for a lark,”5 there was a serious purpose lurking right below the surface. That purpose was to wrest control of the Republican Party from its liberal wing and to do so on its home turf in New York City.

The election in this Democratic city was shaping up to be an important one for the national Republican Party. With few major elections scheduled in odd-numbered years, the 1965 New York City mayoral race would be watched by the nation.

From the perspective of 2015, the Buckley campaign, though launched “half in fun,” had another half that was far more serious. The other half was rooted in the notion that ideas have consequences, that they can change people and politics and can transform society. The great surprise of this campaign was how profoundly transformational these ideas were for the candidate, for New York City, and for the Republican Party and the conservative movement.

* * *

When Buckley announced for the race, the New York Republican Party had already nominated John V. Lindsay as its candidate for the New York mayoralty. Glamorous, handsome, and Yale educated, the forty-three-year-old Lindsay was a four-term congressman from Manhattan’s Upper East Side “Silk Stocking” district. With a voting record in the House that earned him an 85 rating from the left-wing Americans for Democratic Action, Lindsay quickly procured the endorsement of the state’s Liberal Party as well.

For Lindsay, the New York City mayoralty was a way station on the road to the presidency. He had aspirations of taking the Republican Party leftward with him. Buckley, in his unique style, was determined to block these ambitions.

Shortly after announcing his candidacy, Buckley replied to a friend who urged him, for the sake of the Republican Party, not to challenge Lindsay. “It is my judgment,” the new Conservative candidate wrote, “that John Lindsay will do as much harm to the Republican Party if he is elected and becomes powerful as anyone . . . in recent history.”6 Buckley was nearly as blunt in the public statement announcing his candidacy: “Mr. Lindsay’s Republican Party is a rump affair, captive in his and others’ hands, . . . indifferent to the historic role of the Republican Party as standing in opposition to those trends of our time that are championed by the collectivist elements of the Democratic Party.”7

The campaign began with a promise of low effort and high art. Buckley, who had warned the Conservative Party that the race would not disrupt his already crowded schedule, had privately committed no more than a day a week to the effort. To the assembled press, he noted that he expected to campaign when he had time.

From the first press conference, it was clear that he would be running on his own terms. The candidate read his statement of principles in a tone Murray Kempton described as that of “an Edwardian resident commissioner reading aloud the 39 articles of the Anglican establishment to a conscript assemblage of Zulus.”8

Buckley was as committed to enjoying himself as he was to fulfilling his objectives:

Press: Do you want to be mayor, sir?

Buckley: I have never considered it. . . .

Press: How many votes do you expect to get, conservatively speaking?

Buckley: Conservatively speaking, one.9

Within days of launching the campaign, Buckley would make his most lasting contribution to American campaign lore by telling the press that if he were elected, his first action would be to “demand a recount.”10

Joking aside, Buckley had at his disposal one powerful advantage, namely that he “did not expect to win the election, and so could afford to violate the taboos.”11 From the start, his campaign sought to undermine the basic vocabulary of New York City politics: ethnic-group and other bloc voting.

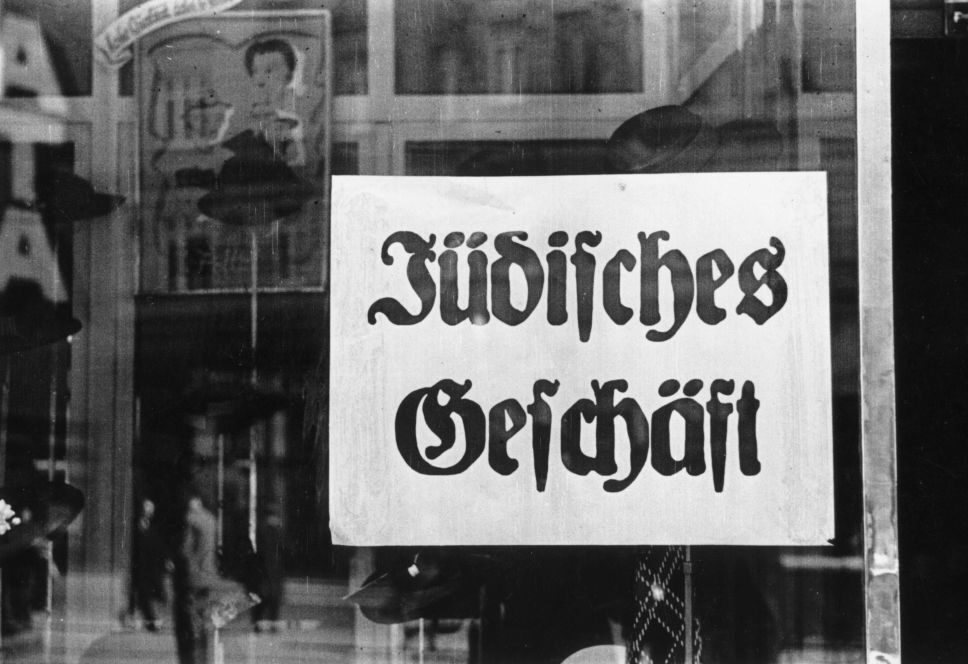

For most of the twentieth century, the Democratic Party’s dominance was rooted in the hundred or so local ethnic clubs—Irish, Italian, Jewish, black, Puerto Rican—that enfranchised recent immigrants and traded votes for municipal jobs and petty graft. By the early 1960s, reform movement Democrats—often from the left wing of the party—had taken over many of the old clubs. But the habits of political affiliation were ingrained in the political culture; ethnic-bloc voting was reality in New York City political life.

Buckley launched a frontal attack on these patterns. Bloc voting of all kinds, he argued, was the enemy of good governance. There was “marginal disutility” involved in appealing to voting blocs; the politician’s desire to satisfy the needs of the largest and most powerful blocs ultimately undermines the welfare of the individual members of those blocs. The taxi driver might enjoy the enforced oligopoly that government provides, but political concessions to other blocs result in higher taxes, greater congestion, weaker schools, and hundreds of problems that ultimately outweigh the value of the oligopoly.

The city’s problems, Buckley claimed, were rooted in maladministration and the capitulation to special interests. Much of the latter could be resolved if politicians engaged voters as individuals, “depriving the voting blocs of their corporate advantages” and “liberat[ing] individual members of those voting blocs.”12 Buckley committed to this idealistic form of campaigning: “I will not go to Jewish centers and eat blintzes,” he declaimed, “nor will I go to Italian centers and pretend to speak Italian.”13

* * *

Through the summer, Buckley’s campaign barely qualified as back-page news. The leading local political story was the September Democratic Party primary, in which City Comptroller Abraham Beame emerged the victor. Other stories occupied the city’s attention: the drought and the New York World’s Fair continued through the summer, and many working-class Catholics were buying televisions so they could witness the pope’s first visit to New York (and America) in early October.

Buckley’s program was scarcely registering with voters until, on September 17, the campaign caught a huge break: the Newspaper Guild called a general strike. The city newspapers, largely in the thrall of the Lindsay campaign, would not publish for twenty-three days. The mayoralty campaign now would be waged on television: in four televised forums, Buckley’s wit, manners, and mercilessly adept debating style transformed him into the central figure in this campaign. “Love him or hate him, TV fans found it difficult to turn off a master political showman,” wrote one scribe,14 while famed campaign chronicler Theodore White deemed Buckley a “star” who would be “Oscar Wilde’s favorite candidate for anything.”15

The effect in the field was even more surprising, especially to those inside the campaign. Television was allowing Buckley’s seemingly academic attack on voting blocs to gain traction not among the intellectual or business class but with the ethnic voters themselves. The largely Catholic ethnic vote—increasingly alienated from both the old and the new reformist clubs—was warming to Buckley’s conservative message of low taxes, individual accountability, and law and order.

“I can tell you that it surprised me,” campaign aide Neal Freeman recalled. “I suppose that I was expecting our supporters to be National Review types—car dealers, academic moles, literate dentists. . . . As soon as we hired halls, though, we learned that [Buckley] was speaking for the people who made the city go—corner-store owners, cops, schoolteachers, first-home owners, firemen, coping parents.”16

The polls showed Buckley rising to 16 percent of the vote—one poll put him at 20 percent—mostly with support from largely disaffected and strongly Catholic voters. Any sense of the campaign’s being a “lark” quickly disappeared, and Buckley, instead of limiting his political activity to a day a week, began to campaign every day.

Buckley’s opponents began to take his campaign seriously, too. After mostly ignoring the Conservative candidate, both Lindsay and Democrat Abe Beame shifted their attacks to Buckley in the campaign’s final days. For Lindsay, it was a matter of survival: polls showed him trailing Beame, and the new attacks on the Conservative were, as the New York Times reported in late October, “an acknowledgment that [Buckley] was a serious threat and could draw off enough votes to cost Mr. Lindsay the election.”17

On Election Day, Lindsay pulled out the victory, with 45 percent to Beame’s 41 percent. Buckley took 13 percent of the vote. Although that represented a decline from his high in October polls, the demographics told an important story. The polls published after the election showed that Buckley won more than 20 percent of his vote from the ethnic Catholic minorities whom the Democrats normally took for granted. In some heavily Catholic districts, his vote grew to 25 and even 30 percent.

The great unintended consequence of the Buckley campaign was the identification of the conservative Catholic vote, a vote that for the first time in modern history was willing to migrate in large numbers from the Democratic Party. Four years later, Kevin Phillips would note Buckley’s success with Catholic voters in his influential book The Emerging Republican Majority.18 As Phillips observed, these results were no “Buckley-linked fluke.” Other conservative candidates for city and statewide offices would make inroads with Catholics. And in 1980, Ronald Reagan would be elected president with a majority of Catholics voting for him. The Catholic swing vote provided Reagan the margin of victory he needed in critical northern industrial states.

* * *

Although the discovery of the conservative Catholic swing vote is the great contribution of the Buckley campaign, the race contributed to the conservative cause on multiple other fronts. Buckley failed in achieving one of his main objectives: defeating his liberal Republican adversary, Lindsay. But his campaign helped wrest control of the state and national Republican Party from Lindsay and other liberals.

In winning the mayoral race, Lindsay claimed almost a quarter of his votes on the Liberal Party line. Buckley, meanwhile, earned 341,000 votes—some 60,000 more than Lindsay claimed on the Liberal line, and nearly three times as many as the Conservative Party’s Senate candidate had won in New York City the previous year. This was the first time the Conservative Party had outpolled the Liberal Party in New York. It marked an important shift, as the Conservative Party endorsement became the most valuable accoutrement for an aspiring Republican candidate. In fact, without conservative support, the incumbent Lindsay failed to get the Republican nomination in 1969. He was reelected mayor as the candidate of the Liberal Party. Thanks in part to Buckley’s campaign, John Lindsay had failed to take the Republican Party to the left, and soon thereafter he abandoned the Republican Party entirely.

The Conservative Party, by contrast, was buoyed by Buckley’s high-profile mayoral campaign. In 1970 the party achieved its first big win: a liberal Republican whom Governor Nelson Rockefeller had appointed to replace the late Senator Robert F. Kennedy was defeated in the general election by James Buckley, the mayoral candidate’s younger brother.

The Buckley mayoral campaign also created the first systematic application of conservative principles to urban problems. Starting with a conservative respect for markets, individual choice, accountability, and localism in politics, Buckley alone drafted all ten of his campaign’s position papers. It is here where Buckley’s skill as a curator of ideas proved most powerful.

On urban development, he wrote, “the beauty of New York is threatened by the schematic designs . . . of social abstractionists . . . who do not . . . recognize what it is that makes for human attachments—to little buildings and shops, to areas of repose and excitement.”19 Here he echoed the words of Jane Jacobs, whose recently published The Death and Life of Great American Cities ultimately became the textbook for smart urban planning.

In the area of race, Buckley adopted the findings of Daniel Patrick Moynihan and Nathan Glazer in Beyond the Melting Pot (1963) and stressed that a sensitivity to family structure was critical to any policy maker’s deliberations on the plight of late-twentieth-century black Americans.

In transportation, he proposed the development of a network of bikeways. The idea was greeted with laughter, but four decades later New York mayor Michael Bloomberg would install hundreds of miles of bike lanes across the city.

The Buckley campaign even toyed with the idea of decriminalization of narcotics, but ultimately backed away in its final position papers.

In a sense, Buckley’s 1965 campaign was a precursor to and inspiration for much of the successful Republican urban policy of the past quarter century. Mayor Rudolph Giuliani and his successor, Bloomberg, each offered a softer and personalized version of Buckley’s urban polity: balancing budgets, advocating personal accountability, making demands of municipal unions, and being tough on crime.

For Buckley, the effect of the campaign was profound. Soon after the election, WOR-TV in New York agreed to syndicate a television program he produced and hosted. The show, Firing Line, would air for more than three decades. In fact, it remains the longest-running public affairs program in television history with a single host. That television exposure helped make Buckley, along with Ronald Reagan, the face of modern conservatism.

* * *

What is often overlooked by the academic historian is the importance of style over substance in political developments. Whereas Barry Goldwater was easy to demonize with his supposed apocalyptic musings, with Buckley (and later Reagan), the charges just wouldn’t stick. “There was a real effort to demonize the right, to treat it as barbaric,” noted one conservative political strategist. “You couldn’t watch Bill Buckley conduct himself and believe that.”20 The Buckley campaign showed that a conservative message, when appropriately styled, could command a stage and engage a reasoned audience, even an adversarial one.

What is most surprising about the Buckley campaign is that it mattered at all. The race wasn’t national, and the candidate was inexperienced and running on a third-party line. But as George F. Will has written, in 1965 “the prestige of government, and government’s confidence, not to say hubris, were at apogees.”21 The two-party system was consolidating around a common idea of governance, and the difference between candidates in many races, as Buckley described his mayoral opponents, “was biological, not political.” In his seemingly quixotic mayoral race, Buckley exposed the inadequacies of this political consensus and helped recall the Republican Party to what, at the campaign’s outset, he described as its “historic role” of “standing in opposition” to centralized government power.

As Will wrote, 1965 proved to be “the hinge of our postwar history.”22 William F. Buckley Jr. played a crucial role in this historic turning point. The Buckley campaign mattered not because it won votes but because it found votes. It reached voters silently disaffected from their heritage party, and with style and reason it seduced them from their historic voting habits. In the process, Buckley helped re-create a thriving two-party system; his efforts would even usher in periods of conservative ascendancy. Goldwater’s postmortem stands true on many levels: Buckley had “lost the election but won the campaign.”23 ♦

Thomas E. Lynch is a former ISI Weaver Fellow who earned graduate degrees from Oxford and Stanford. He is founder and senior managing director of Mill Road Capital.

1 Clare Boothe Luce, National Review, November 15, 1966.

2 As quoted in Sam Tanenhaus, New York Times Magazine, October 2, 2005.

3 Ibid.

4 “There never was, that I know of, a less deliberated, less connived at, less complicated entry into any political race.” William F. Buckley Jr., The Unmaking of a Mayor (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, [1966] 1977), 100.

5 John Judis, William F. Buckley Jr.: Patron Saint of Conservatives (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 249.

6 As quoted in Buckley, The Unmaking of a Mayor, 103.

7 Ibid., 105.

8 Ibid., 114.

9 Ibid., 110–11.

10 Ibid., 120.

11 Ibid., 272.

12 Ibid., 5.

13 Ibid., 120.

14 Edward O’Neill as quoted in ibid., 321.

15 Theodore White, Life, October 29, 1965.

16 Tanenhaus.

17 As quoted in Buckley, The Unmaking of a Mayor, 161.

18 Kevin Phillips, The Emerging Republican Majority (New Rochelle, NY: Arlington House, 1969), 179.

19 Buckley, The Unmaking of a Mayor, 109.

20 As quoted in Sam Roberts, New York Times, March 1, 2008.

21 George F. Will, Public Interest, Fall 1995.

22 Ibid.

23 As quoted in a speech made at the tenth anniversary of National Review.