What is liberty without wisdom and without virtue?

It is the greatest of all possible evils; for it is folly, vice, and madness.

—Edmund Burke, Reflections on the Revolution in France

Western civilization is unique among world cultures in the special significance and value it accords to the idea of freedom.1 Already a central value in Greco-Roman and Christian thought, modern liberalism has exalted freedom as the central human and political value. The effort to secure individual liberty in the religious, political, cultural, and economic spheres lies at the heart of the whole modern project. The liberal doctrine of individual liberties with its intellectual roots in the European Enlightenment of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries is enshrined in the founding documents of the American and French revolutions. America in particular—a nation “conceived in liberty” as Lincoln put it in the Gettysburg Address—has deeply identified itself with the cause of freedom. One of President George W. Bush’s first seemingly spontaneous responses to the 9/11 terrorist attacks was to say that “freedom itself was attacked this morning by a faceless coward.”2

It is left to those gadflies of the world—the philosophers—to raise the awkward question, What does “freedom” mean? The answer is surprisingly elusive. An acquaintance with Western intellectual history reveals that while “freedom” is almost universally lauded as a value, there is no real consensus on its definition. Nevertheless, at least two broadly influential conceptions of freedom have emerged in the Western tradition: one is the modern liberal understanding, and the other took shape in classical Greece. Both ancient Greek and modern liberal thought are complex and involve many variations. Essentially we are speaking of the main emphasis of the modern liberal tradition on the one hand and the tradition of Greek thought that arises from Socrates on the other. With that caveat and at risk of a certain oversimplification we may call these distinctive conceptions “modern freedom” and “ancient freedom.”

What distinguishes the two? Perhaps the most influential account of liberalism’s distinctive concept of freedom came from one of its key twentieth century champions, Isaiah Berlin, who emphasizes the notion of negative freedom as the defining element of the liberal political tradition. This is basically the idea of freedom from external constraint. This seems to be indeed what is ordinarily meant by the civic freedoms of contemporary liberal democracies. One has “freedom of speech” or “freedom of religion” to the degree one can speak as one desires or practice one’s faith without external constraint, especially from the state and its law. Such are the familiar freedoms guaranteed, for instance, by the American Bill of Rights.

We shall argue, however, that this definition is inadequate. The ancients fully understood the notion of negative freedom but believed that freedom considered as merely “unrestrained action” tends to undermine itself, giving birth to tyranny within the soul and within the city. The real distinction then is that the Greek philosophers did not see negative freedom as an end in itself. They warned not only of the tyranny of external constraints but also of the tyranny of the passions. The classical Greek conception is therefore more inclusive and capacious in connecting freedom directly with the question of virtue. The contrasting failure of modern liberalism to relate its idea of freedom intelligibly to any more universal conception of the Good is at the very heart of its present crisis. Excavating the classical conception of freedom will therefore be helpful in raising critical questions about the direction of the modern political order. It is first necessary, however, to provide an adequate account of modern freedom. Turning again to Berlin, in his landmark article “Two Concepts of Liberty,” he explains his notion of “negative liberty” as follows:

I am normally said to be free to the degree to which no man or group of men interferes with my activity. Political liberty in this sense is simply the area within which a man may act unobstructed by others. If I am prevented by others from doing what I can otherwise do, I am to that degree unfree.3

Here is a robust statement of freedom as freedom from external constraint. Liberal thinkers have seen the safeguarding and protection of negative freedom as both the justification of the state (safeguarding individual liberty from encroachment by others) and a concern about government (the threat of the state to the space of negative liberty), and have thus sought constitutional limitations.

What are the origins of “liberalism’s liberty”? It seems to be surprisingly modern as the history of ideas goes. A number of leading thinkers—including Berlin himself—have traced the roots of this dominant modern idea of freedom to Thomas Hobbes in the seventeenth century. As Leo Strauss writes,

If we may call liberalism that political doctrine which regards as the fundamental political fact the rights, as distinguished from the duties, of man, and which identifies the state with the protection or safeguarding of those rights, we must say that the founder of liberalism was Hobbes.4

Despite the fact that the Leviathan is an apologia for a form of authoritarianism, many key elements of Hobbes’s theory were taken up in liberal thought. Hobbes rejects the Aristotelian starting point of man as a political animal, instead building up his political theory from the individual in a state of nature prior to society. In Leviathan, Hobbes provides a pithy definition of freedom:

LIBERTY OR FREEDOME signifieth (properly) the absence of opposition (by Opposition, I mean externall Impediments of motion;) . . . A FREE-MAN, is he, that, in those things, which by his strength and wit he is able to do, is not hindered to do what he has a will to do.5

This is Berlin’s idea of negative liberty—the ability to actualize one’s desires without external hindrance. In essence this would seem to be the dominant notion of freedom in the liberal tradition. For Jeremy Bentham, for example, freedom is merely the space in which man can act without external restraint or coercion:

Liberty is neither more nor less than the absence of coercion. This is the genuine, original, and proper sense of the word Liberty. The idea of it is an idea purely negative. It is not anything produced by positive Law. It exists without Law, and not by means of Law.6

In the pure form of liberalism it would seem then that the ideas of liberty and law are inversely proportional. Liberty is the space wherein action is unimpeded, while law imposes limits on freedom of action. Hence the more man’s actions come under the control of law, the less free he is.

The idea of freedom in classical Greek philosophy by contrast is centered on an ideal of self-mastery.7 The freedom discussed in classical philosophy is not the ability to actualize one’s desires whatever they might happen to be. Freedom is rational self-government—the ability to act according to one’s rational judgment without bondage either to external coercion to the compulsive force exerted by irrational desires and passions. To illustrate the contrast between classical Greek and modern understandings of freedom it might be helpful to think of an alcoholic possessed by a constant, burning desire to drink intemperately. Under what circumstances is this alcoholic free? According to the negative conception of freedom, the alcoholic is free if he is able to drink alcohol as frequently as he wishes without external obstruction. But according to the Greek philosophical tradition, the alcoholic is not a free man but a slave to his cravings. True freedom would mean mastery of his desire.

The great expositor of this concept of freedom is of course Socrates. In Xenophon’s Memorabilia, Socrates asks the rhetorical question:

Then do you think that the man is free who is ruled by bodily desires and is unable to do what is best because of them?8 (Memorabilia 4.5.3)

Plato’s Socrates is the lived embodiment of this idea of freedom as rational self-government as shown by the dignity and sobriety with which he faces death. In the Republic, Socrates argues that a tyrant who might be thought of as the most free of men for being able to actualize all his desires is actually the least free of all men. This is because the highest part of himself—his reason—is tyrannized by his shifting passions and appetites:

Then the tyrannized soul—to speak of the soul as a whole—also will least of all do what it wishes, but being always perforce driven and drawn by the gadfly of desire it will be full of confusion and repentance.9 (Republic 577d–e)

This proposition in book 9 of the work is really the definitive Socratic response to Glaucon’s famous challenge in book 2—why is it better to be just and suffer the consequences of injustice than to be unjust and receive the rewards of justice? The answer is that the evil and the unjust are slaves of the lowest parts of human nature, and thus the most miserable of men. Injustice is its own punishment—for it is in itself slavery.

It would seem therefore that the relationship of freedom to virtue and the good is one of the principal ways in which classical and modern freedom can be distinguished. If freedom is defined negatively as merely unobstructed action, it is evident that negative freedom can be used either for good or for evil. In short, negative freedom would seem to be morally neutral. This can be clearly seen in the freedoms of liberal societies. Take for example “freedom of speech”—it can be used to promote acts of benevolence and justice; equally it can used to mass-produce pornography, immerse crucifixes in urine, or insult the grieving families of dead soldiers.

By contrast, it is through the moral disciplines that one acquires freedom in the Greek philosophical conception. The acquisition of courage frees one from slavery to fear, liberality frees from slavery to the lust for money and wealth, temperance from slavery to alcohol and sexual lust, and the same with the other vices. In the Greek view one is free only to the precise degree one has acquired the virtues. Freedom and virtue therefore exist in a necessary relationship. Indeed freedom as self-mastery is the very foundation of the virtuous life. Turning again to Xenophon’s Socrates:

Should not every man hold self-control to be the foundation of all virtue, and first lay this foundation firmly in his soul? For who without this can learn any good or practice it worthily? Or what man that is the slave of his pleasures is not in an evil plight body and soul alike? (Memorabilia 1.5.4–5)

However, the Greek philosophical tradition is not insouciant about the meaning and importance of negative freedom. This especially is the case with Aristotle, who considers negative freedom a necessary condition for virtue. The “objectively” good act if not done freely but in ignorance or under compulsion is not an act of virtue at all:

. . . the virtues themselves are not done justly or temperately if they themselves are of a certain sort, but only if the agent also is in a certain state of mind when he does them: first he must act with knowledge; secondly he must deliberately choose the act, and choose it for its own sake; and thirdly the act must spring from a fixed and permanent disposition of character.10 (Nic. Ethics 1105a–b)

But of course negative freedom is not a sufficient condition of virtue, since one can deliberately choose the evil or base as well as the good and noble. The good life will consist in the “active exercise of the soul’s faculties in conformity to rational principle” (ibid. 1098a) and will therefore be related to the rational government of the passions. The Aristotelian approach recognizes the place of negative freedom; but unlike that liberal tradition that places it at the top of the hierarchy of values, Aristotle subordinates negative freedom to a conception of the good life. The virtuous man acts without compulsion but also in accord with right reason. Thus the value of negative freedom is its relationship to moral excellence.

A consequence of the distinction is the radical difference in how the Greeks and modern liberals think about the broader political order. In the classical liberal view represented, for example, by Locke, government is based on a contract simply for “the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates which, I call by the general name, property.”11 For Aristotle this would seem a limited and vulgar view of the end of politics, since man has a nobler end than the mere preservation of his life and personal property. Concerning the political community, its “object is not military alliance for defense against injury by anybody, and it does not exist for the sake of trade and business relations” (Politics 1280a),12 for these are not concerned with moral character and virtue in general but only with protection from mutual injury. But as Aristotle argues:

All those on the other hand who are concerned about good government do take civic virtue and vice into their purview. Thus it is also clear that any state that is truly so called and is not a state merely in name must pay attention to virtue; for otherwise the community becomes merely an alliance. (Politics 1280b)

For Aristotle the end of politics is therefore conditioned by a teleological conception of the end of man in general—namely the realization of the good or virtuous life. Man attains this end in the context of the political community. In the classical view expressed by Aristotle, it is not the protection of a merely negative freedom of each individual to live as he wishes that constitutes the end and justification of politics but freedom in the sense of rational and virtuous self-mastery.

Negative freedom also appears as a value within Athenian politics. Each citizen had a measure of “free speech” that was thought necessary for the proper exercise of his deliberative function within the life of the polis. A special term, “frank speaking” (parrhesia), was used to distinguish this form of liberty from the more usual term (eleutheria).13 Testimonies to this idea are found in Greek drama, rhetoric, and philosophy. In his Hippolytus, Euripides has his character Phaedra state that she gave birth to her children “that they may live in glorious Athens as free men, free of speech and flourishing.”14 This freedom was defended in particular by the great rhetoricians who being thoroughly immersed in the political life of the city realized its essential importance. Demosthenes in his Exordia admonishes the Athenians:

I think it is your duty, men of Athens, when deliberating about such important matters to allow freedom of speech [parrhesia] to every one of your counselors.15

The assumption is that wise deliberations on matters of law and policy cannot take place in an atmosphere of terror and repression in which everyone fears to speak his mind. This freedom must be defended, for Demosthenes, against the tyrannical ends of Phillip of Macedon, for “it would be monstrous if the freedom of utterance which is the privilege of this platform would be stifled by dispatches from him.”16

Socrates himself recognizes the value of free debate and free inquiry not only in the life of the polis but also in the dialectical process of philosophical inquiry. In these words to Polus in the Gorgias he states:

It would indeed be a hard fate for you, my excellent friend, if having come to Athens, where there is more freedom of speech than anywhere else in Greece, you should be the one person who could not enjoy it.17 (Gorgias 461e)

Still, the Greek philosophers were ambivalent about the emphasis on a purely negative freedom in Greek democracy, fearing that without a moral foundation it could easily degenerate into license. This perspective is strongest in Plato, who views democracy as the penultimate stage in the decay of the polis, and disparages democratic humanity:

To begin with, are they not free? And is not the city chock-full of liberty and freedom of speech? And has not every man license to do as he likes? . . . and where there is such license, it is obvious that everyone would arrange a plan for living his own life in the way that pleases him. (Republic 557b)

Thus democracy for Plato is essentially indifferent on the question of virtue and vice—all modes of life enter into the polis in a position of equality. The liberation of all desires and appetites, moreover, overturns social order and leads to a condition of lawless anarchy that eventually culminates in tyranny—the least free and least virtuous of all political forms:

“The same malady,” I said, “that, arising in oligarchy, destroyed it, this more widely diffused and more violent as a result of this license, enslaves democracy. And in truth any excess is wont to bring about a corresponding reaction, . . . most especially in political societies. . . . Probably then tyranny develops out of no other constitution than democracy—from the height of liberty, I take it . . . the fiercest extreme of servitude.” (Ibid. 563e)

Aristotle also sees freedom as a value particularly associated with democracy:

Now a fundamental principle of the democratic form of constitution is liberty—that is what is usually asserted, implying that only under this constitution do men participate in liberty, for they assert this as the aim of every democracy. (Politics 1317b)

The conception of liberty that Aristotle considers democracies to possess contains two elements—first there is the right of the ruled also to rule, and, second, in democracy there is an ideal “for a man to live as he likes” (Aristotle, my italics). The vulgar conception of freedom is therefore purely negative—acting on one’s desires without externally imposed restraints. Aristotle, however, like Socrates and Plato is sharply critical of this view of freedom for its essential amorality. Aristotle argues that “liberty to do whatever one likes cannot guard against the evil which is in every man’s character” (Politics 1319a).

What is the relationship of this classical concept of freedom to Christianity—the world religion that displaced the ancient Greco-Roman gods and presented itself as the saving truth that sets men free (John 8:32)? A full development of this broad theme lies outside the scope of this essay, but a few issues merit mention. Since Christianity arises initially from Hebrew rather than Hellenic roots, the relation between Christian and classical views of freedom raises for us the vexed problem of “Athens and Jerusalem,” which permeates almost all aspects of the Western civilizational tradition. Some philosophers have argued for a basic incompatibility between the claims of Greek philosophy and those of the Bible. As Leo Strauss, for example, argued:

So philosophy in its original and full sense is then certainly incompatible with the Biblical way of life. Philosophy and the Bible are the alternatives or the antagonists in the drama of the human soul. Each of the two antagonists claims to know or to hold the truth, the decisive truth. The truth regarding the right way of life. But there can only be one truth: hence conflict between these claims and necessary conflict among thinking beings; and that inevitably means argument.18

Is this the case, however, on the issue of freedom? Consider the words of St. Paul:

For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I do. Now if I do what I do not want, it is no longer I that do it but sin which dwells in me. . . . For I delight in the law of God in my inmost self, but I see in my members another law at war with the law of my mind and making me captive to the law of sin which dwells in my members. Wretched man that I am! Who will deliver me from this body of death?” (Romans 7:21–24)

Man’s fundamental condition in the fallen state is here considered as one of slavery to sin. Thus we see that both the Socratic and the Christian understandings conceive the absence of freedom as enslavement to those self-centered passions and desires that obstruct the only worthy freedom of man—the freedom that leads to moral rectitude.

While on close analysis there are certain differences between the Christian religious understanding of sin and the Greek philosophical notion of vice, there is an even broader harmony. The major difference resides not in the definition of freedom but rather in the question of how freedom can be achieved. For St. Paul man is unable to free himself from sinful passions by his own power, but depends for his liberation on a supernatural intervention—the grace of God manifested in Jesus Christ. For the Greeks, by contrast, the acquisition of virtue remains fully in the natural and human sphere—a matter of the right philosophical understanding of the Good and the moral discipline of the virtues.

However, the Roman Catholic Church in particular embraced the synthesis of St. Thomas Aquinas, who aimed to reconcile Christianity and Aristotelianism by arguing for both a distinction and a harmony between natural virtue, which lies within human power, and supernatural or theological virtue, which requires grace.19 At all events, Christianity introduced no essential challenge to the fundamental classical understanding of freedom, but on important points confirmed it. Its principal contribution was to relate the idea of freedom to the supernatural order. The Christian faith can be interpreted in a manner that moves the question of freedom into a new religious-theological frame without overthrowing the concept of natural virtue in which the classics are invested.

Still, Christianity, with its concept of man’s eternal destiny, necessarily limits the total claims of the classical polis over the human person and gives rise to a new conception of the free personality who can stand in conscience against the state where it oversteps the boundaries of its legitimate authority. This notion is probably a historical precondition for the rise of modern liberalism, which, however, exaggerates Christian personalism into a radicalized concept of human autonomy. The linchpin of liberalism is the individual’s absolute right over himself, which frees him from the claims of political and religious authority. The most formidable of Enlightenment philosophers, Immanuel Kant, famously attacked heteronomy—any law that is not self-legislated—as “the source of all spurious principles of morality.”20 Likewise in the English-speaking world, John Stuart Mill argues, “In the part which concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”21

Given the frequency with which states have been meddlesome, repressive, and at times murderous toward their citizens, liberalism’s defense of personal autonomy is intelligible; and arguably the human need for privacy and, within limits, simply “to be left alone” merits a place in the hierarchy of values greater than what was articulated in classical political thought. But social conservatives will note the ways in which a radicalized idea of autonomy has also been a keystone of modern cultural nihilism. Abortion and euthanasia are defended precisely by the liberal notion that “Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”22 The idea of the sovereign individual leads almost inexorably to the notion that individuals have the right to define the Good for themselves, and consequently the view that any notion of the universal Good that would bind human conduct is an unacceptable constraint on autonomy.

* * *

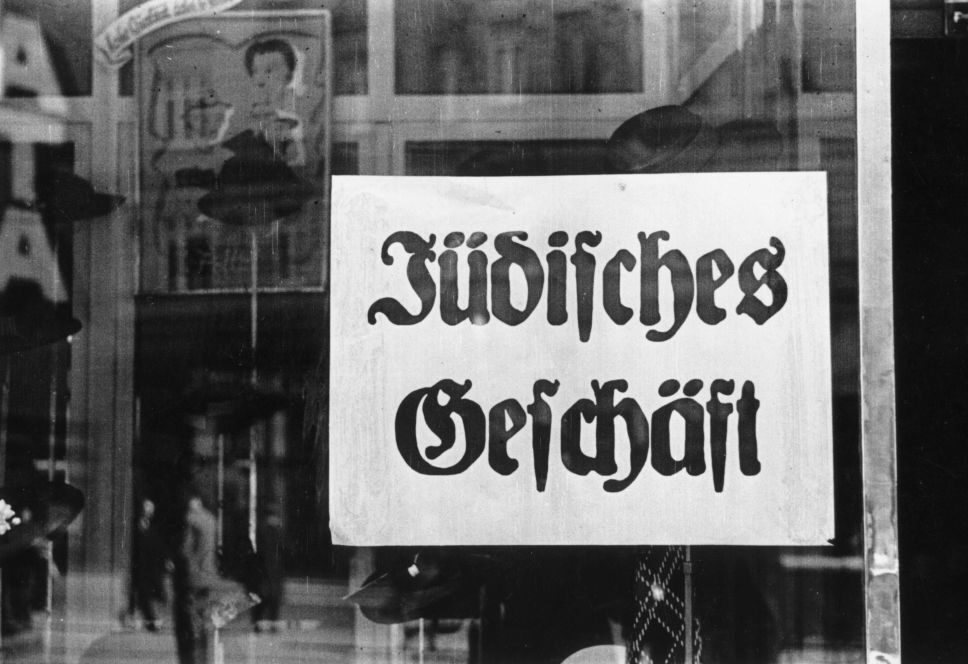

This problem of the relationship between liberalism and moral relativism has been a central issue to modern political thought as witnessed in the work of Isaiah Berlin and Leo Strauss. Liberalism wishes to defend the freedom of each individual to live according to his own values without external interference. As such, the idea of a universal Good becomes suspect in liberal societies; for if there is a good life, true and valid for all mankind, then the character of individual choices must be measured against the degree to which they realize this universal Good. If Plato saw in the idea of each man pursuing his own conception of good the seeds of anarchy, modern liberals have instead argued that the idea of an overarching universal Good contains the seeds of tyranny. The fear—underlined by the historical reality of modern totalitarianism—is that in the name of realizing a Good that will make human beings “truly” free, coercion may be employed by those who feel they have greater insight into the Good against those they regard as ignorant. As Berlin frames the matter:

I may declare that they [the objects of coercion] are actually aiming at what they in their benighted state actually resist . . . their latest rational will or their “true” purpose. . . . Once I take this view, I am in a position to ignore the actual wishes of men and societies, to bully, oppress, torture them, in the name, and on the behalf, of their “real” selves in the secure knowledge that whatever is the true goal of man (happiness, performance of duty, wisdom, a just society, self-fulfillment) must be identical with his freedom—the free choice of his “true,” albeit submerged and inarticulate, self.23

To avert this danger Berlin and other defenders of the liberal tradition propose a rejection of the very concept of an overarching Good that human nature as such ought to realize. Berlin’s position is that belief in such an overarching Good contains the implicit temptation to impose this concept on the unwilling—an idea he associates with modern totalitarianism. Individuals must be free not only to act without interference but also to seek and define their own values. This is his famous concept of value pluralism:

Pluralism, with the measure of “negative liberty” it entails, seems to me a truer and more humane goal than the goals of those who seek in the great, disciplined, authoritarian structures the ideal of “positive” self-mastery. . . . To assume that all values can be graded on one scale, so that it is a mere matter of inspection to determine the highest, seems to me to falsify our knowledge that men are free agents.24

Liberalism—at any rate as Berlin articulates it—has an argument against the classical conception of the Good that arises therefore from its individualism: its desire is to defend the individual and his negative freedom from any notions of the political Good that may impose on the right of the individual to shape his life according to his own norms.

This point is central to Leo Strauss’s concern about the direction of modern liberalism,25 namely, the tendency of liberalism to become relativistic and therefore to undermine itself. Liberalism tends to individualize the concept of “the Good” by asserting that it is the individual who is best positioned to define the Good relative to his own individual life. This idea when thought through, however, tends to abolish the whole concept of the Good, since individual conceptions of the Good are bound not only to differ but also to contradict each other. This position can only be consistently maintained if one denies that any conception of the Good corresponds to the truth. In this case no conception of the Good can be allowed to claim an absolute and universal validity for all. Liberalism is thus tempted to uphold freedom by setting it against the notion of the universal Good.

But at the point at which it argues for the equal validity of individually defined and mutually contradictory conceptions of the Good, it is led by its logic into the temptation of relativism. When one examines the macabre historical course of the first half of the twentieth century in Europe, the rapid mutation of the liberal into the totalitarian state in Germany, Italy, and elsewhere, is it not possible to perceive the metastasis of a conceptual pathology that grew up within the matrix of liberalism itself? If no values can claim absolute validity, then on what grounds can liberalism claim greater truth or validity than illiberal values? If the notion of “the Good” is entirely relative, then there is no foundation to the claim that liberalism is the best form of governance, or that free societies (however defined) are in any sense superior to unfree societies. Relativism is the true source of the totalitarian temptation in modernity and not the classical conceptions of virtue. In the words of one historian:

The avowed philosophy of totalitarian regimes (like much of modern thought) was basically subjective. Whether an idea was held to be good depended on whose idea it was. Ideas of truth, beauty or right were not supposed to correspond to any outer or objective reality . . . no norm of human utterance remained except political expediency—the wishes and self-interest of those in power.26

Moreover, the vices decried by Western religious and social conservatives in modern liberal society—the disdain for human life reflected in the abortion culture, spread of euthanasia, the mass industry of pornography and promotion of hedonism and violence in popular culture, the breakdown of the family—seem all to be consequences of an inadequate concept of freedom, which fails to relate it to any broader conception of the Good. The aimlessness of modern freedom, which glorifies unrestrained action without regard to its moral character, increasingly resembles the vulgarized freedom decried by Plato when he asked with indignation, “Has not every man license to do whatever he wants?”27

The main lesson then, which we derive from the ancients, is that freedom when set against reason and virtue is self-negating. The individual or society given to an unrestrained license yields immediately to the despotism of the passions and eventually to the despotism of state-imposed constraints. The disorders of the soul beget disorders in the commonwealth, which eventually require greater measures of coercive power to keep them within bounds.28 True freedom is won and sustained by virtue. This insight of the classics occurs as well in the modern conservative tradition. As articulated by Edmund Burke:

Men are qualified for civil liberty in exact proportion to their disposition to put moral chains upon their appetites. . . . Society cannot exist unless a controlling power upon will and appetite be placed somewhere; and the less of it there is within, the more there must be without. It is ordained in the eternal constitution of things, that men of intemperate minds cannot be free. Their passions forge their fetters.29

Of course liberalism also echoes important values of the Western political tradition, such as freedom of thought and inquiry and bringing the power of the state under the restraint of law. Reengagement with the classical political tradition would mean not doing away with these values but integrating them into a broader and more coherent ethical structure.

That the limited concept of freedom conceived as mere absence of constraint on the desires of the sovereign self has proved popular—and indeed had been raised to an absolute value—is unsurprising. It is evident that freedom as understood by the Greek philosophers is not easy but difficult; it requires an intense and painstaking moral discipline to liberate oneself from the passions and achieve rational self-mastery. Inevitably this challenging conception falters in winning mass popularity against a notion of freedom adjusted to the unhindered satisfaction of human appetites and desires. But for the Greek philosophers, mass popularity was never a criterion of truth. Their concept of freedom is aristocratic in the original and genuine sense of being concerned with the cultivation of moral and intellectual excellence. ♦

Alexander Rosenthal-Pubúl is an online lecturer in political thought at Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Advanced Governmental Studies from his home in Spain. He is also cofounder and director of the Petrarch Institute, which is dedicated to keeping alive the classical humanist tradition.

1 I would like to thank Dr. John Hymers and Richard Evans for their assistance in reviewing the text. This essay was inspired by my blog post “Two Ideals of Freedom: Classical Greece and Modern Liberalism” on the Johns Hopkins blog Govstud, http://www.governmentalstudies.com/govstud/2013/3/4/two-ideals-of-freedom-classical-greece-and-modern-liberalism.html (accessed 12/26/13). Note that biblical quotations are from the New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha—Revised Standard Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977). Stephanus numbers are used in inline text for Plato, and Bekker numbers for Aristotle.

2 http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/gwbush911barksdale.htm (accessed 3/21/2014).

3 Isaiah Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” in Four Concepts of Liberty (New York: Oxford University Press, 1969), 122. Hereafter Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty.”

4 Leo Strauss. Natural Right and History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), 181–82.

5 Thomas Hobbes, “Of the Liberty of Subjects,” chap. 2 in Leviathan, https://ia800303.us.archive.org/21/items/hobbessleviathan00hobbuoft/hobbessleviathan00hobbuoft.pdf.

6 Jeremy Bentham, University College Papers 69.44, quoted in Frederick Rosen, Classical Utilitarianism from Hume to Mill (New York: Routledge, 2003), 247 (accessed via Google Books, 9/17/2013).

7 See the discussion in Werner Jaeger, Paidea: The Ideals of Greek Culture, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1963), 53ff, and also the footnotes on p. 379.

8 Xenophon, Memorabilia, ed. E. C. Marchant (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1923), http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/ (accessed 11/12/2013). Hereafter Memorabilia.

9 Plato, Republic, books 6–10, trans. Paul Shorey (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), hereafter Republic.

10 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

11 John Locke, Second Treatise of Government, bk. 2, chap. 9, http://www.johnlocke.net/john-locke-works/two-treatises-of-government-book-ii/ (accessed 10/5/2013).

12 Aristotle, Politics, trans. H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005).

13 Cf. the discussion of parrhesia in Michel Foucault’s Berkeley lectures on the topic, which can be accessed here: http://foucault.info/documents/parrhesia/foucault.dt1.wordparrhesia.en.html (accessed 3/22/2014).

14 Euripides, Hippolytus 4:22, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Eur.%20Hipp.%20422&lang=original (accessed 12/17/2013), bracketed Greek text added.

15 Demosthenes, Exordia 27.1, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0068%3Aexordium%3D27%3Asection%3D1 (accessed 12/12/2013). My addition of the Greek term.

16 Demosthenes, On Halonesus 7.1, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0070:speech=7:section=1&highlight=freedom (accessed 12/12/2013).

17 Plato, Lysis, Symposium, Gorgias, trans. W. R. M. Lamb (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996).

18 Leo Strauss, “The Mutual Influence of Theology and Philosophy,” Independent Journal of Philosophy 3 (1979; rpt. of 1954 article): 114, http://deakinphilosophicalsociety.com/texts/strauss/theologyandphilosophy.pdf (accessed 12/3/13).

19 See St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica I-II.62.1, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Westminster, MD: Christian Classics, 1981).

20 Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, trans., M. Gregor (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 47, 4:441.

21 John Stuart Mill, On Liberty, ed. John Gray (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 14.

22 Mill, On Liberty.

23 Berlin, “Two Concepts of Liberty,” 133.

24 Ibid., 171.

25 Leo Strauss “Relativism,” in Thomas Pangle, The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press), 13–26.

26 R. R. Palmer and Joel Colton, History of the Modern World, 4th ed. (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1971), 874.

27 Plato, Republic.

28 See Russell Kirk, “The Moral Imagination,” in Literature and Belief, vol. 1 (1981), 37–49, http://www.kirkcenter.org/index.php/detail/the-moral-imagination/.

29 Edmund Burke, “Letter to a Member of the National Assembly,” http://www.gutenberg.org/files/15700/15700-h/15700-h.htm#MEMBER_OF_THE_NATIONAL_ASSEMBLY (accessed 3/21/2014).