The Conservatarian Manifesto: Libertarians, Conservatives, and the Fight for the Right’s Future

By Charles C. W. Cooke

(New York: Crown Forum, 2015)

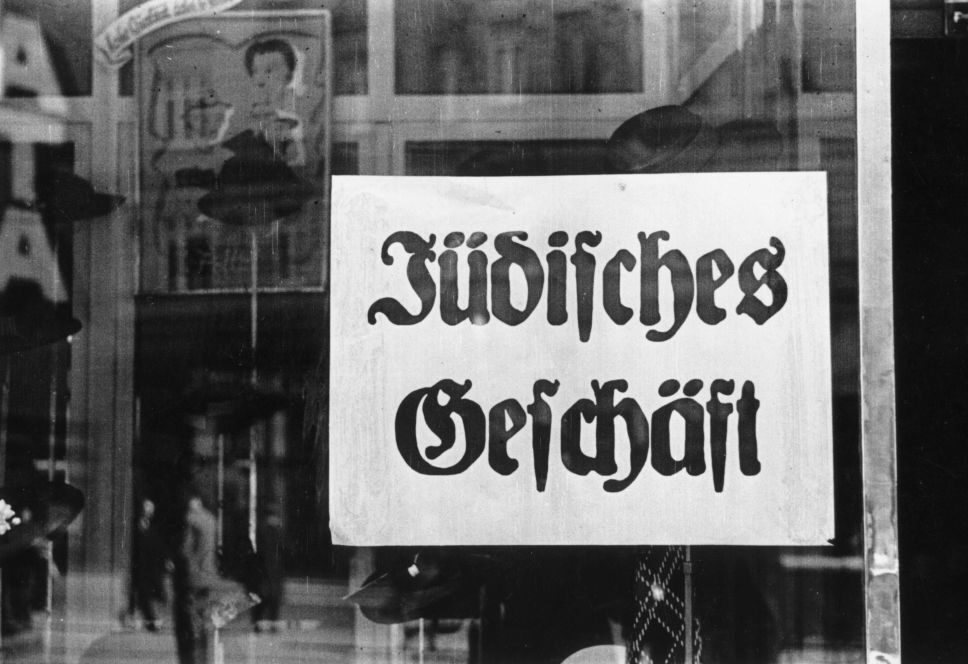

The thoughtful Charles C.. W. Cooke is a British émigré to the United States, an Oxford graduate in modern history and politics, now writing for National Review. He looks forward to becoming an American citizen. His political thought is like that of Daniel Hannan, the UK Conservative member of the European Parliament and author of Inventing Freedom, but Cooke’s focus is the American scene. Their particular British perspective sees the United States as a magnificent part of a broader, particularly Anglo story, a part especially remarkable for its inceptive classical liberal ethos and constitutional system of divisions, brakes, and bindings on government power, and whose classical liberal character is, tragically, being destroyed, especially by Democrats and leftists generally.

With a sober understanding of the state of affairs in Europe, Cooke captures the feeling after the 2012 election in the United States:

Politics being a zero-sum game, the prevailing take was that the Republican Party was destined to go the way of the Whigs—powerless in the face of demographic change, unable to match the unassailable Democratic coalition, and years behind a deep-seated ideological switch that had pushed the United States away from the center right and towards the temptations of social democracy. If the GOP continued on its course, it would end up as a rump regional party. Sure, if the Republicans made some leftward changes and rode the political pendulum, they would likely hold office in the future. But they would not effect substantial change. Like conservative parties in other countries, the role of Republicans in American life would henceforth be to manage the welfare state better than does the Left, to slow the pace of change, and to blunt the sharp excesses of a dominant progressivism. (12)

Cooke and I have arrived independently at the position that current political discourse is distorted by the abuse of the term liberal (see Modern Age, Summer 2015). Cooke, like Daniel Hannan, makes a point of not calling leftists “liberals” and describes his thinking as “classical liberal.”

Neologisms typically horrify, and “conservatarian” is no exception. After finishing Cooke’s book, I felt the neologism to be something of an afterthought, and the book’s subtitle, “Libertarians, Conservatives, and the Fight for the Right’s Future,” to be more fitting than the main title. Cooke does not much use the term conservatarian but speaks, rather, of conservatives and libertarians. Cooke’s central aim is perhaps like that of Frank Meyer and Grover Norquist, namely, to get good policy—or, at least, better policy—to work as good politics. The vehicle of the good politics, for Cooke, is the constellation of discourse, organization, media, mobilization, governing, and so on that I shall call “Team Republican.”

Cooke speaks principally to conservatives, or Team Republican, but also to libertarians. He wants to persuade conservatives of two things: First, that, generally speaking, good policy is policy that is quite libertarian; his most significant case is the folly and evil of the war on drugs. And second, that good politics, for Team Republican, is politics that seriously upholds a presumption of liberty. So Cooke holds that better policy can be good politics. He argues, I think persuasively, that Republicans would renew their liberty luster and gain support by taking the lead in drug liberalization.

Speaking to libertarians, Cooke has parallel aims. Cooke wants to persuade them that good policy is not always as formulaically libertarian as they might think. A key theme here, arising notably in discussions of foreign policy and immigration, is that a policy that augments liberty directly, such as downsizing and withdrawing the military or opening the borders to all comers, might have consequences that reduce liberty indirectly, and enough to spell a reduction in liberty overall. Cooke illuminates the idea that augmentations in direct liberty may sometimes produce reductions in overall liberty.

Cooke recognizes that policy debate and policymaking proceed, not on the basis of absolutes, but upon presumptions, like the presumption of innocence. It’s not that everyone is innocent, but that the burden of proof is on the prosecution. Cooke aims to persuade libertarians that any responsible political thought must recognize, not only a presumption of liberty, but also a presumption of the status quo. He insists repeatedly that policy discourse should be anchored in the status quo.

When confronting a reform proposal that would reduce liberty, such as enacting Obamacare or hiking the minimum wage, the two presumptions—the one of liberty, the other of the status quo—happily agree on where to locate the burden of proof: on the liberty-reducing reformer. But for reforms that would augment liberty, such as liberalizing drug policy or abolishing the minimum wage, the two presumptions disagree: the presumption of liberty places the burden of proof on the defender of the liberty-trenching status quo, while the presumption of the status quo places the burden of proof on the liberalizing reformer.

Cooke rightly suggests that libertarians are sometimes irresponsible in failing to see that social life necessarily privileges the status quo to some degree; responsibility demands that one strike some balance between the presumption of liberty and the presumption of status quo. Cooke wants to persuade libertarians that striking such a balance need not subvert a presumption of liberty; rather, his brand of classical liberalism, conservatarianism, strives to make a presumption of liberty essential to Team Republican, where it is often lacking.

By cultivating conservatarianism within Team Republican, Cooke seeks to cool the hostility between conservatives and libertarians. Cooke contends that conservatarianism (or classical liberalism) is the soul of Republican conservatism, starting from, say, 1912, when Woodrow Wilson began to contribute so mightily to the character of the opposing party. Particularly good is his chapter on the Constitution and the American Founding, including the compromise with slavery. Cooke projects a narrative that classical liberalism is the political outlook that conservatism seeks to conserve. He quotes Ronald Reagan: “The very heart and soul of conservatism is libertarianism.”

His narrative is that there was an era in which classical liberalism was ascendant; it was the status quo philosophy, if not the status quo policy; but beginning particularly in the late nineteenth century, collectivists like Wilson wanted to reform the philosophy and policy of the status quo, mostly in ways that would reduce liberty. At that time, since the reforms sought were mostly reductions in liberty, the presumption of liberty and the presumption of the status quo stood shoulder by shoulder against surging statism.

The days of classical liberal ascendency are long gone; we need to recognize today’s status quo for what it is, and the resultant paradox in the term conservative: The world over, conservative suggests a strong presumption of the status quo, but now the status quo is generally not to conservatives’ liking. Furthermore, Cooke blasts Republicans-in-practice, particularly during the George W. Bush years. His contention for the soul of Republican conservatism is really an aspirational one: he points to the possibility of a possibility. Cooke tells Team Republican that, with care and intelligence, the Team can claim its soul to have been classically liberal all along. The chapters to come can write those of the past.

Cooke writes about guns, drugs, same-sex marriage, abortion, foreign policy, immigration, federalism, and judicial activism, and freely states his positions and arguments. His arguments are often concise and powerful, thereby assuring the reader of his depth on the issue. But his concern is not so much with the rightness of his position as with conservatarianism as good politics. The principal purpose is not to establish what is good policy but rather to address how better policy can be good politics.

Although Cooke contends that conservatarianism is, or can be, the soul of conservative Republicanism, there is another way to read his book: perhaps it isn’t the soul, but at least it deserves a welcome and respected place within the big tent of Team Republican. Just as the Team welcomes social conservatives, it should also warmly welcome conservatarians. Welcoming this breed will grow support for the Team, as libertarians will come to feel they have an accepted, respected place within the tent.

I find Cooke’s discussion of the various issues to be consistently insightful, informative, and sensible. There is one part I find disappointing, however—that on abortion. Cooke says that, here, good politics lies in moderation, and I agree. But he also makes admirably clear his own preferred view and position. It is that “life” clearly and plainly starts at conception, and that abortion clearly and plainly is “killing.” What’s more, those judgments, Cooke suggests, clearly and plainly imply that abortion is murder. Before finishing the chapter, I said to myself: “Hmm, notwithstanding the fact that Cooke is a Brit out of Oxford, and a supporter of same-sex marriage, I guess he is some sort of serious Christian.” But a page or so later, as though he had heard my thought, Cooke describes himself as an atheist.

In sum, I admire Cooke’s book greatly. He affirms the hope that better policy can be good politics. We really have little choice but to hope that hope. But serving that hope, even maintaining it, is trying. It requires getting political agents, including politicians, opinion leaders, and voters, to see and favor better policy, and it requires getting wise and effective policy analysts, first, to keep up the production and articulation of such analysis, and, second, to do so in a way that may influence political agents.

Adam Smith commented on character in magistrates and lawmakers. He made a place for an admirable type, “the man of public spirit”: “When he cannot establish the right, he will not disdain to ameliorate the wrong; but like Solon, when he cannot establish the best system of laws, he will endeavour to establish the best that the people can bear.” Showing Solonic virtue, Cooke’s book combines policy wisdom and responsible concerns for political effectiveness. ♦

Daniel B. Klein is professor of economics and JIN Chair at the Mercatus Center, George Mason University.