America and the Political Philosophy of Common Sense

by Scott Philip Segrest

(Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2010)

With this bold and well-written work, Scott Philip Segrest—an instructor in American politics at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point—makes a bid to join the conservative tradition of German refugee, philosopher of history, and political thinker Eric Voegelin (1901–1985). He sees his work as an explicit effort to fulfill Voegelin’s suggestion that “someone write a history of the common sense tradition,” which Voegelin discovered in the early 1920s in the course of attending pragmatist John Dewey’s Columbia University lectures on the American and British tradition of philosophy. Throughout his work, Segrest repeatedly affirms Voegelin’s main proposition that the transcendent is found within the operation of human spirit and civilization’s search for order.

In addition to his primary goals of defining the worth of the commonsense school of thought, establishing it as distinctly embodied in the American political tradition, and acknowledging that the commonsense tradition was significantly anticipated by Aristotle’s epistemology and shared common ground with eighteenth-century natural rights advocates like Jefferson, Segrest contends that the school was best given form by three American protagonists, the first two of whom were illustrious Scottish immigrants who, the cream of a thriving Scottish university education, were outstanding students of philosophy and divinity, and Presbyterian ministers as well.

The first of these Scots, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, John Witherspoon (1723–1794), was invited in midlife to serve as president of Princeton College in the 1760s. The second, James McCosh (1811–1894), became president of the same college, almost exactly one hundred years later. The third, psychologist and philosopher William James of New England, gave the commonsense tradition a fresh and enduring vitality.

As both a creator and representative of the commonsense tradition in America, John Witherspoon was influenced by such commonsense progenitors as philosophers the third Earl of Shaftesbury, Francis Hutcheson, and especially Thomas Reid. As heir of that tradition, Witherspoon challenged Hume’s skepticism, which reduced ideas to a posteriori additions to sensations and experience, and denied intuitions of God and truths of conscience that go with elemental construction of meaning. On similar grounds, Witherspoon attacked preeminent Enlightenment philosopher Immanuel Kant. In criticizing Hume, Kant mistakenly conceived truth as contingent on a priori impositions of space, time, and cause on sense experience—and conceived the moral good as predicated on a duty resting on a universalized goodwill toward all humanity, which stands beyond circumstances and is independent of interests of self, others, and community.

Even more pertinent to the articulation of the commonsense tradition, Witherspoon, according to Segrest, extended his critique to Locke’s philosophy, challenging its epistemological dependence on sensory empiricism and an ethics derived from laissez-faire political liberalism. While he agreed that democratic politics is about ensuring and exercising rights, Witherspoon reproved Locke for his compact based on individual rights and Hobbes for one rooted in survival, and argued for a broader covenant based on recognizing and balancing interests, rights, and other activities, along with reciprocal duties to community and obligations to God. A slave owner himself, Witherspoon denounced the domination and ownership of workers. He even supported revolution when rulers did not use government to extend protection to the weak. He signed the Declaration of Independence on the grounds that Britain confiscated property and took away the fruits of industry and means of life.

Witherspoon as a philosopher stood in essential agreement with Aristotle, Aquinas, and the classic tradition of natural law. He recognized the benefits for freedom and order of a good constitution, established law, and the making and keeping of contracts for ensuring the practice and habits that produce a wholesome morality. Witherspoon identified “the importance of law in American political self-understanding . . . not a merely utilitarian calculation in the service of narrow self-interest but a moral imperative imposed by the ‘laws of nature and of nature’s God.’ ”

“The good man, the good citizen, and the good society,” Witherspoon wrote, “will take account of interest and utility but will, in the end, always make these legitimate concerns conform to what conscience demands.”

James McCosh, Segrest’s second representative, came to Princeton in 1868. He arrived as a well-known professor and a minister identified with the reformation movement within the Church of Scotland. Having fought valiantly for the establishment of the Free Church, McCosh went on to make his mark as professor of philosophy. His essay on Stoic philosophy had made a stir in 1833. When John Stuart Mill’s System of Logic appeared in 1843, McCosh took issue with Mill’s apparent refusal to give due weight to supernatural powers and counterattacked in 1850 with his own lively volume, The Method of Divine Government, Physical and Moral, which was instrumental in leading to his appointment to the Chair of Logic and Metaphysics at Queen’s College, Belfast, founded by the British government “for the promotion of nonsectarian education.”

Segrest joins the work of Witherspoon and McCosh with the spirit and continuity of a historical period that, according to Alexis de Tocqueville, was a religious time. In this age, Segrest writes, “the American mind corresponds closely in time and in substance with the reign of Scottish realism in the American academy.” On this historical foundation, Segrest favorably reconstructs McCosh’s extraordinary account of the nature and operation of certain first intuitions. McCosh, Segrest argues, correctly criticized Kant and Mill for not articulating how conceptions of mind and body, personal identity, causation, and moral obligation reside within perception itself.

Segrest sees limits, however, to McCosh’s political and ethical thought. As profoundly as he probed the abstractions of Kantian ethics and individualism, McCosh did not open himself to a dynamic life or a changing America. Rather, in the end he retreated, according to Segrest, to a conscience cloistered in orthodox Presbyterianism, leaving it for Segrest’s hero, William James, to herald an energetic and transformative ethics and politics.

Indeed, the commanding premise of Segrest’s work is that the turn-of-the-nineteenth-century American philosopher and psychologist William James singularly renewed commonsense philosophy and revitalized American thought. In formulating pragmatism and revitalizing the commonsense and natural rights tradition, James converted an American understanding of life into a philosophy. With reference to the central historicist tenet of early-eighteenth-century Italian thinker Giambattista Vico’s verum factum, Segrest claims that James left the realm of thought for action by contending that man knows and makes himself in and across time as an embodied, acting, and self-defining creature.

Preparing him for passage from the nineteenth to the twentieth century, Segrest labels James a master phenomenologist who laid the basis for an existential pragmatism. James not only elevated human consciousness from the immediacy of awareness but also conceived it as a sum of all previous experience (memory) as it resides in the act of perception, conception, judgment, and will. And though “perfectly in line with Scottish Common Sense philosophy,” James, according to Segrest, “differs in two crucial and momentous respects:

(1) in understanding the intellectual modes of thinking that compose common sense to be ancient habits [italics mine!] rather than the products of permanent structures of the mind; and in neglecting or treating inadequately the intuition of first principles.”

On this abstract epistemological basis, Segrest concludes that James did nothing less than reenergize both the commonsense and American political traditions by preparing its followers to enter the world on all levels; and they can make their entrance with inexhaustible hope of serving self, others, and nation without loss of freedom, reason, values, and God.

Segrest’s claims for James strike me as exaggerated. How, I ask, can Segrest make James, though admittedly an embodied thinker, a singularly important renovator of the American ethical and political tradition when James didn’t write about politics? Why, in fact, didn’t James at least incorporate his philosophy into subsequent political practice and ideology? And even more to the point, hasn’t Segrest overlooked the obvious fact that James’s lifetime obsession, as both his passion and curse, was to make sense out of the interior, not the public, life?

Furthermore, Segrest’s case for James’s importance for vibrant democracy is not well buttressed. Although an advocate of freedom and individuality, isn’t James, like Nietzsche, Bergson, and so many other intellectuals but another fin de siècle critic of the advent of mass society? Segrest also does not advance the case for James’s originality or contemporary relevance by arguing that the philosopher believed that society’s strongest tradition and chance for innovation depended on elites whose energy, vision, and commitment should be fostered by education. Finally, a case for James’s relevance to the American political tradition cannot be made in light of his rejection of the widespread fin de siècle malaise, which he himself suffered. Indeed, despite Segrest’s efforts, James is not entirely spared an intellectual affinity with younger French and German generations that marched off enthusiastically to the First World War, especially in view of historian George Cotkin’s affirmation that James “called for st[r]enuosity, passion, and heroism . . . [his philosophy] served as a jeremiad and solution to social lethargy, to the numbing tedium vitae that James believed afflicted many Americans in the late-nineteenth-century.”

As much as Segrest succeeds in putting forward his important thesis that James as “philosopher keeps us close to reality and in its living truth rings the present relevance of the common sense tradition,” the question remains whether his assessment of James arises from careful historical analysis or a willed philosophical conclusion. As much as I appreciate how Segrest excels in the latter, I believe that he has failed the test of writing embodied history.

This wish to speak of historical relevance without writing history shows throughout his work. At the outset, Segrest does not offer a critical inventory of the commonsense tradition and its proponents (especially Scottish and Presbyterian thinkers) in the Colonies. He does not distinguish traditions and types of natural rights thinkers (so important to the life and work of Leo Strauss!) so that we might identify and distinguish the thought of Jefferson and other eighteenth-century signers of the Declaration and drafters of the Constitution. But far more than this, Segrest’s assumption that theoretical philosophy, analytic ethics, and academic psychology (at which Witherspoon, McCosh, and quintessentially James excelled) are at the heart of the American political tradition needs to be explicitly argued. In making his case, Segrest had to reject other suitors for the heart of American ethics and politics, such as the long-standing colonial practice and tradition of local control and the common law.

At the same time, Segrest’s indispensable assumption that there was and is a unique and singular American political tradition raises questions (in the spirit of such conservative-liberal thinkers as Burke, Tocqueville, Acton, and Russell Kirk) about its dependence on broader Western cultural and philosophical achievements. For example, I would, without differentiation, include traditions of toleration, local autonomy, individual and communal rights, and law as articulated in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Reformation, and further by religious and secular thinkers across the emergent early-modern and modern Atlantic community.

In place of his provincial predilection and philosophical proclivity to join the American tradition to select and speculative Founding Fathers, Segrest (perhaps beyond the bounds of any one monograph) must at least concede that at all points, American ethical and political thought is pluralistic and stands in both dependent and reciprocal relations to diverse currents of European thought. This interplay does not cease with the Revolution and Constitution but continues right from the start of the nineteenth century, with romanticism, the formation of German historicism, the articulations of idealism and transcendentalism, influences of positivism, naturalism, Darwinism, German academicism, and the formation of academic natural and social sciences, all of which find their way into idea-hungry American libraries and schools and eventually onto the plate of the voracious William James.

Finally, I note the omission from Segrest’s work a reference to James’s great contemporary Henry Adams (1838–1918). A true historian who was equally at home in the White House, American embassies, the halls of European learning, and the Western outpost of the nation’s westward expansion and Pacific imperialism, Adams wrote definitive volumes on the formation of the fledgling republic under Madison’s and Jefferson’s presidencies. Unlike James, who was not equipped to do so, Adams suffered the fate and politics of the nation—not just its plutocracy and mass democracy but also its accelerating revolutions of technology, which were embodied for him at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago by the dynamo. He speculated about a nation, not to mention mankind, accumulating power not just over nature and beyond the control of its politics but beyond the very range of its metaphors to order and value its experience.

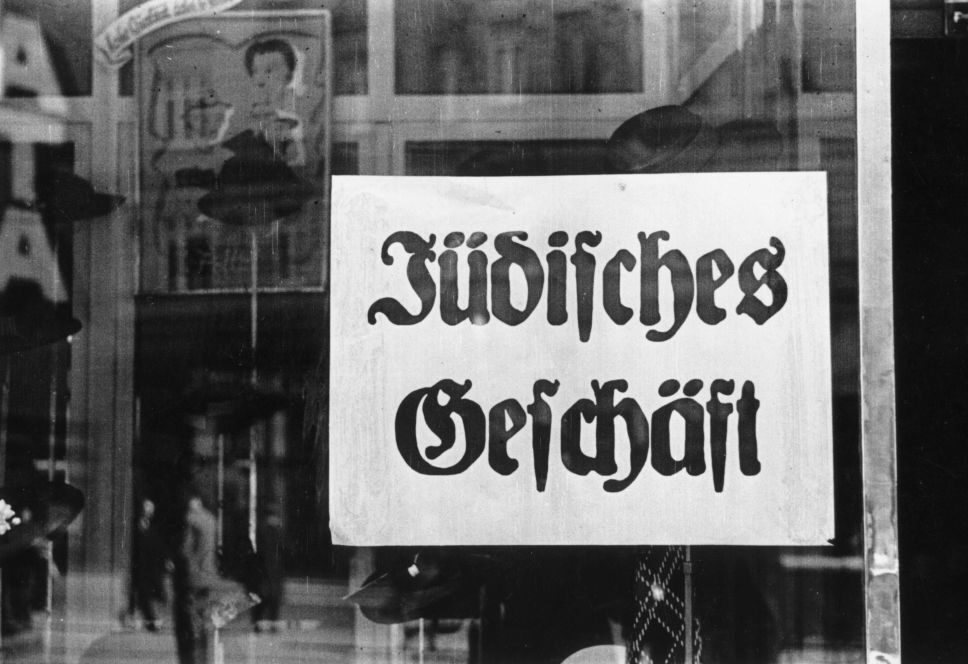

Because Segrest chooses James over Adams, he misses confronting what I take to be the central question: Do any twentieth-century intellectual and political traditions have a language (metaphors of human being, action, order, and God) to compass the dramatic events come upon us? At the same time, he forces me to ask how James’s (or Segrest’s, for that matter) belated effort at renewal could exceed multiple and diverse previous contemporary attempts of both political Left and Right to renew democracy—either in the United States, Europe, or elsewhere? (I think for example of previous efforts at intellectual renovatio made by the Action française, diverse youth movements, Fascism and National Socialism, refurbished types of secularism, socialism, and Marxism, as well as conservative platforms established on the assumptions and principles of Burke, Tocqueville, and others.)

I admire this work for what it intelligently and lucidly affirms—an epistemology based on form and being; an ethics based on equal primacy of religion, conscience, community; and a politics that, though with excess, finds a singularity of worth and experience in American history. I appreciate its attempt in the spirit of Voegelin to turn political discourse in the direction of being and knowing. But in the end Segrest’s thesis strikes me as too abstract and ahistorical to prove vital in this era of all-encompassing globalism, encapsulating technologies, and the raw and unexpected course of unfolding events. Left with little promise of establishing a common philosophical ground, perhaps we can do no more than reason within the bounds of conscience, freedom, and justice; act with goodwill, a capacity for compromise, and restraint; and cherish the hopes and prayers we can muster for nation, democratic tradition, and world. ♦

Joseph Amato is professor emeritus of history at Southwest State University. His most recent book is Jacob’s Well: A Case for Rethinking Family History.