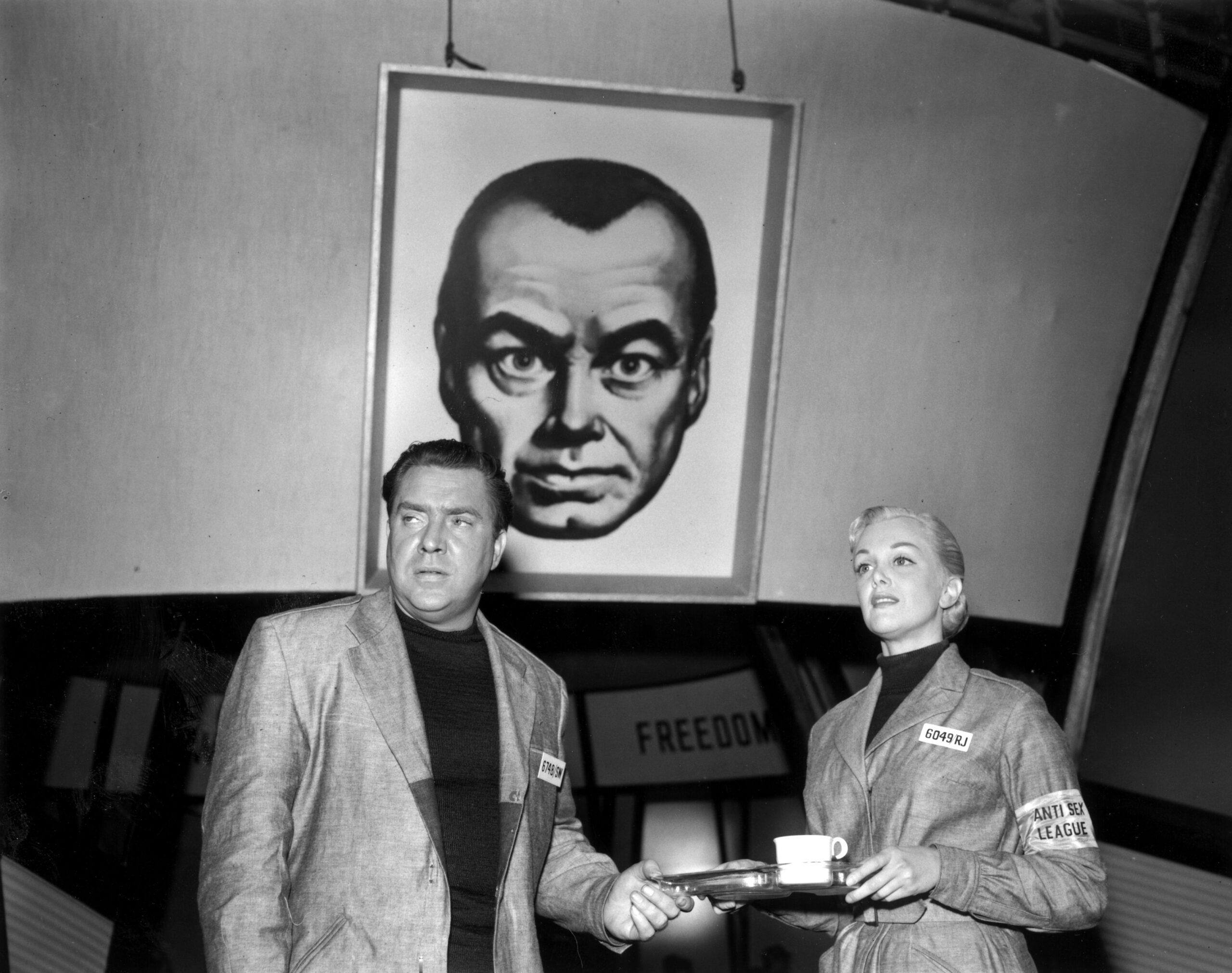

To the end of his life, George Orwell remained a socialist. In “Why I Write” (1946), we find his programmatic statement: “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic Socialism, as I understand it.”1 Orwell had fiercely attacked the attitude of capitalist society towards the poor in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) and in The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). He always made a point of wearing the blue shirt of the French working class.2 And in the last summer of Orwell’s life (1949) he enrolled his adopted son Richard in the anarchist colony at Whiteway.3 Of 1984 specifically, Orwell wrote to Francis Henson: “My recent novel is NOT intended as an attack on Socialism or on the British Labour Party (of which I am a supporter). . . .”4

Yet if Orwell remained in his own mind a man of the Left (indeed, the far Left), a paradox appears if we survey the references to the capitalist “past” in his last and greatest work. The capitalist “past” of 1984 is, of course, to a great extent Orwell’s present. And seen from the nightmare world of Ingsoc, the capitalist “past” has much to recommend it—in fact, just about everything to recommend it.

There are two outstanding characteristics of this vanished “past.” First, material life for the average person had been far better in the “past” than under Ingsoc. Examples are numerous: the wide availability of real coffee, real sugar, real chocolate, good beer, wine, fruit, solidly built furniture, elevators that worked.5 Above all: the wide availability of well-made books and even objects kept for their intrinsic beauty alone.6

Second, in the “past” there had existed individual freedom: freedom of thought, human rights, even freedom of speech. The total suppression of human freedom under Ingsoc is, of course, the main theme of 1984 and needs no detailing. But that such freedom had once existed Orwell is careful in the novel to make clear: we are not dealing here with mere theoretical human possibilities. In the “past,” then, it had been usual for people to read books in the cozy and complete privacy of their own homes—without fear of the Thought Police.7 In the “past” people had kept diaries, to record events and thoughts for themselves: this had been taken for granted.8 In the “past” human relationships had existed naturally, without constant state interference—which is why the life of intimacy and honesty lived by Winston Smith and Julia above the old junk shop is explicitly called a relic of an earlier age.9 In the “past” there had been no imprisonment without trial, no public executions, no torture to extract confessions.10 In the “past” orators espousing all sorts of political opinions had even had their free public say in Hyde Park.11

And from Goldstein’s Book Orwell’s hero Winston Smith learns that the previous existence of relative plenty and relative individual freedom had not come about by accident. Relative plenty had resulted from the increasing use of industrial machines in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, which in turn had led to wider distribution of goods and very greatly increased standards of living.12 Relative individual freedom had prevailed because

The heirs of the French, English and American revolutions had partly believed their own phrases about the rights of man, freedom of speech, equality before the law . . . and had even allowed their conduct to be influenced by them to some extent.13

Capitalism, according to the Party, had meant a world of poverty and slavery.14 In the course of the first part of 1984, Winston Smith’s varied historical research—interviews, the collecting of artifacts, and the reading of Goldstein’s Book—reveal to him that this is a lie.15 The capitalist “past” had not been perfect: prosperity and freedom had been only partial.16 But obviously, the previous capitalist civilization had been beyond measure preferable to the current Ingsoc State. Conversely, Winston comes to see that it is Ingsoc itself which is responsible for the current conditions of poverty and slavery.17

It is at least in part this “lost civilization” that Winston toasts in the famous scene in which he and Julia are inducted into the (bogus) underground resistance movement:

“What shall it be this time?” [O’Brien said]. “To the confusion of the Thought Police? To the death of Big Brother? To humanity? To the future?” “To the past,” said Winston.18

“To the past.” Winston’s point may partly be to celebrate a past that is in general unalterable and sacrosanct, despite the cynical slogan of the Party on this matter. Perhaps, too, Winston’s toast is an indirect expression of Orwell’s well-known nostalgia for the English past of his own childhood. However, the most direct reference here seems to be to the specific “lost past” of England before the Ingsoc Revolution—for that is the (capitalist) “past” which Winston throughout the whole first part of the novel has been attempting, with desperate intensity, to rediscover.

Since Orwell was a socialist, this basically positive depiction of “past” capitalist society in 1984 represents a problem. And the problem is compounded by a closer examination of the Henson letter. Orwell explains, as we noted above, that 1984 is not intended as an attack on socialism; yet in the very next phrase he also says that the book is intended as “a show-up of the perversions to which a centralised economy is liable.”19 Thus, a convinced socialist has written a book in which the effects of a centralized, planned economy are socially disastrous and in which capitalist society appears quite attractive—especially (but not solely) by contrast. The first element here can probably be explained as an outgrowth of Orwell’s ongoing dispute in the 1940s with the authoritarian Left—the communists and their supporters within the English intelligentsia. But the second element is even more intriguing, since, strictly speaking, it is unnecessary to the theme of the novel. That is, there was simply no need for Orwell to portray the “past” capitalist world so attractively in order to condemn the brutal totalitarianism of the Ingsoc State. We are dealing here at least partly with an ambivalence—even a contradiction—in Orwell’s attitude towards capitalism: or so I will argue. Basically, Orwell despised capitalism; but especially in his most pessimistic moods, he was willing to concede it a crucial virtue.

In Orwell’s original forebodings about the destruction of civilization (1933), the engine of destruction would be Huxley’s “Fordification”: capitalism and consumerism. The population of the world would be reduced to docile wage-slaves, their lives utterly in the hands of “the bankers.”20 Under the impact of the cataclysmic events of the 1930s, however—the coming of Hitler, the Soviet purge trials, his experience in the Spanish Civil War—a different vision eventually began to impose itself on Orwell. By 1938 he was coming to fear that civilization would be destroyed by the worldwide triumph of state dictatorship.21

The first truly detailed exposition of Orwell’s dark vision of eventual worldwide totalitarianism occurs in his essay on Henry Miller: “Inside the Whale” (written in the summer and autumn of 1939; published in March 1940). In seeking to explain the political quietism of Miller’s writing, Orwell argues that an inevitable historical process is leading to the destruction of “western civilization”—which he defines as laissez-faire capitalism and liberal-Christian culture.22 What is coming is the centralized state, and the new world war will only hasten its arrival. But the implications of this development have not been fully understood, Orwell says, because people have falsely imagined that socialism would most likely be a better form of liberalism.23 On the contrary: “almost certainly we are moving into an age of totalitarian dictatorships,” an age in which both freedom of thought and the autonomous individual will be stamped out of existence.24 But this in turn means that “literature, in the form we have known it, must suffer at least a temporary death”—for literature has depended on the existence of the autonomous individual writer.25 In the present a writer may well choose to aid the coming of the new age, but he cannot contribute to this political process as a writer, “for as a writer he is a liberal, and what is happening is the destruction of liberalism.”26 Hence Henry Miller’s political quietism. As a writer—as a liberal—the only honest subject left to him in this age of violent political change is personal life (sex).27

In this essay Orwell emphasizes that western literature has depended upon individual freedom of thought, and that both have depended upon the existence of a “liberal-Christian culture”—which is disappearing, in favor of the centralized state. No direct link is made as yet between literature and the existence of capitalism as a specific economic system. There are hints in that direction, but only hints (laissez-faire capitalism is paired with liberal-Christian culture as essential to the definition of “western civilization”; and the autonomous, honest writer is described as “a hangover from the bourgeois age”).28 Nor is Orwell against socialism: the centralized state which is now coming may be grim, but it may also be a grim necessity. This is why Orwell allows writers to participate in the struggle to bring about the new world (although, he emphasizes, not as writers). And Orwell does not completely abandon hope that this new world might eventually produce its own great literature (of a new sort, it is true). He ends the essay with the assertion that Miller’s political quietism demonstrates the impossibility of any major literature “until the world has shaken itself into its new shape.”29

Still, this is only a small ray of light in an otherwise very dark landscape. In fact, Orwell’s publisher, Victor Gollancz, a man of strong left-wing views, was upset with “Inside the Whale” and wrote Orwell that he was being too pessimistic about the future. Orwell replied (January 4, 1940):

You are perhaps right in thinking I am over pessimistic. It is quite possible that freedom of thought etc. may survive in an economically totalitarian society. We can’t tell until a collectivised economy has been tried out in a western country.30

But at the moment, Orwell continues, he is more worried about intellectuals stupidly equating British democracy with fascism or despotism: given the current threat from Germany, he hopes that the common people will have more sense.31

For us there are three points to note in this important letter. First, Orwell at this time clearly is not fully pessimistic about the effect of a collectivized state on intellectual freedom. Second, we see that Orwell (perhaps at Gollancz’s prodding) is indeed exploring in his mind the relationship between freedom of thought and the specific form of economic life within a society. And we can see his unease with the idea that society might be both “economically totalitarian” and intellectually free: it is possible, but somehow not logical. Third, Orwell brings Gollancz back from theory to reality, firmly asserting the value of the freedoms currently existing in Britain: capitalist Britain is not a fascist despotism and deserves defending by everyone. This was an idea that set Orwell apart from many leftist intellectuals, and it was still relatively new within Orwell himself. Well into 1939 he had continued to equate British “democracy” with fascism—the position he now castigated in others.32 But with the coming of war with the Nazis, Orwell had experienced a sudden, monumental awakening of sentimental patriotism,33 and this letter to Gollancz shows that it included an appreciation of the freedoms Britain actually provided. Those freedoms formed the reality against which Orwell would henceforth judge socialist theory. Perhaps the effect can already be seen in “Inside the Whale,” where we find not merely the vision of a totalitarian future (in Orwell’s thoughts since at least 1938), but also a true elegy for “liberal-Christian culture.”

If in the Gollancz letter Orwell is uncertain about the fate of intellectual freedom in a collectivized economy, nine months later he is definitely optimistic. In “The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius” (written in the autumn of 1940; published in February 1941), Orwell proposes a revolutionary program, including nationalization of industry and equalization of incomes through punitive taxation.34 The capitalist system is doomed in any case, Orwell writes, and socialism is necessary if Britain hopes to win the war.35 But, he asserts, his socialist regime will not degenerate into tyranny, because it will be solidly grounded in the prevailing gentleness of English culture.36 This idea seems to be an amplification of Orwell’s remarks to Gollancz about the possibility of a humane—western—economic collectivism, combined with Orwell’s new, patriotic approval of the basic forms of English life.

And it is probably no accident that, hopeful of an English and democratic socialism, Orwell now is explicitly disdainful of economic liberty per se. In modern England,

the liberty of the individual is still believed in, almost as in the nineteenth century. But this has nothing to do with economic liberty, the right to exploit others for profit.37

Even in “The Lion and the Unicorn,” though, Orwell’s direct criticisms of English capitalist society are quite restrained. Basically, it is economically too disorganized to cope with the current military crisis (Orwell believes centralized coordination and control will be necessary for that), and it produces an upper class which is too stupid to win the war.38 But Orwell declares also that capitalism has spread prosperity much further down the social scale than was previously thought possible.39 And with all its faults, British society is not a fascist dictatorship. Its claim to be democratic is not a complete sham, nor its claim to respect human rights:

In England, such concepts as justice, liberty and objective truth are still believed in. They may be illusions, but they are powerful illusions. The belief in them influences conduct, national life is different because of them. In proof of which, look about you. Where are the rubber truncheons, where is the castor oil?40

This passage—and especially the idea that the prevailing belief in legal justice and liberty tends strongly to influence bourgeois social conduct—points directly ahead to “Goldstein’s” explanation of relative human freedom in capitalist society before the Ingsoc Revolution.41 The prevailing English liberty and legality are precisely what Orwell believes his proposed English socialist state—efficient, but gentle—will preserve.

Orwell’s confident mood of 1940—the odd euphoria of the Battle of Britain—did not last long, however. He soon relapsed into pessimism. Even before “The Lion and the Unicorn” came out in print, his hopes for an immediate, democratic socialist revolution had already faded.42 Moreover, Britain was still fighting practically alone against Nazi Germany, and in the spring of 1941 the war news was genuinely terrible. England now seemed to Orwell to be on the verge of losing the war; at the very least, a long grim struggle was in the offing, with untold negative effects on the relatively benign character of English society. Thus, we find him writing in his diary on May 18, 1941: “Within two years we shall either be conquered or we shall be a socialist republic fighting for its life, with a secret police force and half the population starving.”43

Britain defeated (or even occupied), Britain a starving socialist police state: this had not been the vision of 1940. Renewed pessimism about the future now led Orwell to an even sharper appreciation of the virtue of the present than he had displayed in the Gollancz letter and in “The Lion and the Unicorn.” The result: two essays, in April and May 1941, which are of significance in the development of Orwell’s thought, but which have never received more than glancing attention from Orwell scholars. Because it is far more accessible to American students of Orwell, and because his “other” view of capitalism is expressed most clearly in it, I will concentrate on the second of these two essays: “Literature and Totalitarianism.” However, some of the ideas here are foreshadowed a month earlier, in the startlingly titled “Will Freedom Die with Capitalism?”44

“Literature and Totalitarianism” originated as a radio talk for the BBC Overseas Service and was then published in The Listener. It appears that Orwell was somewhat self-deprecatory about these BBC radio lectures. But the problem was not their content. Orwell simply felt guilty about beaming discussions of British literary culture to India at a time when India was struggling to gain her independence from Britain.45 The lecture “Literature and Totalitarianism” was broadcast on May 21, 1941—that is, just three days after Orwell had filled his diary with the darkest forebodings about the English future. In fact, “Literature and Totalitarianism” is the second full-scale exposition of Orwell’s nightmare vision of worldwide tyranny (the first being “Inside the Whale”).

Orwell begins by explaining that European literature over the past four hundred years has been the product of the autonomous individual, concerned only to write with honesty.46 But in “the age of the totalitarian state,” which is likely to be a worldwide phenomenon, the individual is not going to be allowed any freedom whatever.47 And the origin of the totalitarian state, Orwell now says, is basically economic: the end of “free capitalism” and its replacement by “a centralised economy.”48 The result:

The economic liberty of the individual, and to a great extent his liberty to do what he likes . . . comes to an end. Now, till recently the implications of this were not foreseen. It was never fully realised that the disappearance of economic liberty would have any effect on intellectual liberty. Socialism was usually thought of as a sort of moralised liberalism. The state would take charge of your economic life, and set you free from the fear of poverty . . . but it would have no need to interfere with your private intellectual life. . . . Now, on the existing evidence, one must admit that these ideas have been falsified. Totalitarianism has abolished freedom of thought to an extent unheard of in any previous age. . . . Can literature survive in such an atmosphere? . . . It cannot. If totalitarianism becomes world-wide and permanent, what we have known as literature must come to an end. And it will not do—as may appear plausible at first—to say that what will come to an end is merely the literature of post-Renaissance Europe.49

This is an astonishing passage. The linking of economic liberty with other liberties represents a complete reversal from Orwell’s position in “The Lion and the Unicorn.” The explicit connecting of economic liberty with intellectual liberty, the explicit connecting of centralized control over the economy with centralized control over the private intellect—this is an analysis worthy of Norman Podhoretz. (In fact, it is the analysis of Norman Podhoretz, and precisely in an article about Orwell—but without reference to “Literature and Totalitarianism,” so little known is this essay.50)

Much of “Literature and Totalitarianism,” clearly, is based on ideas we first encountered in “Inside the Whale.” But there are at least two significant changes. First, the existence of the honest and autonomous author, and thus of literature as we have known it, is now attributed not to “liberal-Christian culture” (as in “Inside the Whale”), but precisely to the existence of economic liberty itself. Second, a centralized economy, once it becomes totalitarian, will not mean just the death of “bourgeois literature” (as in “Inside the Whale”), but of literature, period.

Orwell does try to sound a hopeful note at the end, but the attempt only reveals his current despair. Literature’s survival, he says, depends on those countries where liberalism has sunk its deepest roots:

Though a collectivised economy is bound to come, those countries [may] know how to evolve a form of Socialism which is not totalitarian, in which freedom of thought can survive the disappearance of economic liberty.51

But this idea—which lay at the heart of “The Lion and the Unicorn”—is now called a mere “pious hope”; and Orwell ends his exposition with the dry comment: “That, at any rate, is the only hope to which anyone who cares about literature can cling.”52 He clearly fears that here he is merely whistling past the graveyard. Even gentle Britain was not immune from socialist totalitarianism, as he had already written in his diary. That, of course, is also one of Orwell’s main points in 1984 (and consciously intended to shock), as he explicitly says in the Henson letter.53

Now, after “Literature and Totalitarianism,” Orwell never returned to an explicit, full-scale discussion of the connection between economic liberty and intellectual freedom. This is at first sight odd, for Orwell was a writer capable of repeating an idea ad nauseam. The reason for his reticence here seems obvious, however: the implications of this view of the social impact of capitalist economics made Orwell the socialist very uncomfortable, challenging his most cherished ideals about how a “just” society should look. Those ideals he never gave up. Nevertheless, the ideas evolved in the face of the catastrophe that seemed to loom in spring 1941 had an enduring influence upon his life and work. The simplest evidence comes from the Henson letter and has already been quoted: 1984 is “a show-up of the perversions to which a centralised economy is liable.”54 The emphasis here on the economic origins of Big Brother points directly back to “Literature and Totalitarianism.”

It is also striking that after 1941 Orwell occasionally wrote passages extolling nineteenth-century capitalism and capitalist society as phenomena characterized, above all, by human freedom. The most famous instance occurs in “Riding Down to Bangor” (1946). In discussing the mood of certain mid-Victorian American novels, Orwell remarks:

They have not only innocence but . . . a buoyant, carefree feeling, which was the product, presumably, of the unheard of freedom and security which nineteenth-century America enjoyed. . . . [It] was a rich, empty country . . . in which the twin nightmares that beset every modern man, the nightmare of unemployment and the nightmare of State interference, had hardly come into being. . . . There was not, as there is now, an all-prevailing sense of helplessness. There was room for everybody, and if you worked hard you could be certain of a living—could even be certain of growing rich; this was generally believed, and for the greater part of the population it was even broadly true. In other words, the civilisation of nineteenth-century America was capitalist civilisation at its best.55

Such outright praise of anything is rare in Orwell.

Orwell returned more than once to this theme of the nineteenth century as an age of human freedom.56 And after 1941 we also find occasional brief remarks where he links capitalism directly or indirectly with liberty (especially intellectual liberty).57 He praised unregulated, independent small businessmen, too; and he came to use the term “capitalist democracy” without irony (unusual in a man of the far Left).58

This is not to suggest that Orwell’s view of capitalism ever became basically positive. On the contrary. Whatever his occasionally idealizing (and even naive) attitude towards a stage of capitalism in the past, Orwell feared and despised what he saw as the giant “monopoly” capitalism of the present. As powerful and as impersonal as the State, it was just as capable of crushing the individual—through the unemployment line, rather than the interrogation chamber.59

By the early 1940s Orwell had also become deeply suspicious of economic collectivism per se: especially the threat it posed to intellectual freedom. As the Henson letter shows, this suspicion never faded. Similarly, Orwell had come to fear the implications of the growing power of the State over society. Indeed, Orwell feared the State more than he feared capitalism—perhaps because he continued to feel that the capitalist system was dying, while he worried that the age of the State was only beginning. Clearly, it was difficult to reconcile these attitudes with his advocacy of socialism, for socialism inevitably involves some form of economic collectivism, as well as an expansion of government control over society: and Orwell understood his conflict here perfectly well.60 The difficulty may help account for the general “paleness” of Orwell’s prosocialist writing after 1941. It is a fact that it is singularly lacking in concrete and convincing detail either about the shape of a democratic socialist society or how we are to get there. This is particularly true of his proposed Socialist United States of Europe—while in the real world Orwell sided with America (faute de mieux) in the Cold War and castigated intellectuals who did not do the same.61 Indeed, after 1941 Orwell’s real focus of social concern changed radically: he concentrated his literary energies more and more simply on the defense of civil liberties and intellectual freedom. He had come to see how fragile these things were and from how many directions they were threatened.62 Orwell’s friend T. R. Fyvel now tells us that when the postwar Labour government began nationalization of industry and punitive taxation of incomes two of the very measures which Orwell himself had proposed in “The Lion and the Unicorn”—Orwell “was not against these measures[!] . . . only he had become profoundly suspicious of any extension of state power.”63 How deeply Orwell had changed since the euphoria of 1940. Fyvel believes that Orwell always remained a socialist—and then at the last moment he introduces a crucial qualification: “he was formally a socialist.”64

If Orwell was “formally a socialist,” what was he really? Obviously, a complicated and sometimes self-contradictory human being. Fyvel concludes that more than anything else, Orwell was a pessimist; and this is in line with the final judgment of another of Orwell’s friends, Herbert Read.65 In pointing to the polarity between socialism and pessimism in Orwell’s thought, Alan Zwerdling has put Orwell’s dilemma this way: although Orwell claimed to retain faith that a democratic socialism could somehow be achieved, his critique of the statist tendencies within the socialist movement was devastating to him, and “a hopeless faith is a contradiction in terms.”66 My point is in a way the reverse of Zwerdling’s, but also complements it: Orwell’s moods of pessimism made him not only more wary of socialism, but also less hostile to capitalism and capitalist society.

But I would also suggest that besides the polarity of socialism/pessimism, there was another polarity in Orwell’s thought. As a political person he was (or considered himself) a socialist, but as a writer he was a liberal. I am not the first to describe Orwell as a liberal; indeed, both George Woodcock and Bertrand Russell even call him a “nineteenth-century liberal.”67 But I mean the term in the specific way Orwell himself used it, the way he felt was vital to a writer: “liberty-loving,” especially regarding freedom of thought.68 Thus, as a writer—as a liberal—Orwell intensely valued liberal and tolerant surroundings, valued the relatively liberal and tolerant surroundings provided by bourgeois England, and feared that economic collectivism would lead to the destruction of liberalism and toleration. I would suggest that this fear which Orwell felt as a writer eventually came to balance the ideals of “social justice” and economic equality which he upheld as a (democratic) socialist. This goes a long way towards explaining the special emphasis in 1984 on the destruction of autonomous thought by the Party, the emphasis on the (collectivist) economic origins of Ingsoc society, and, conversely, the novel’s depiction of pre-revolutionary capitalist society as basically benign.

But, of course, socialist and writer were one man. And Orwell himself was well aware of the fundamental ambivalence into which he had fallen:

If one thinks of the artist as . . . an autonomous individual who owes nothing to society, then the golden age of the artist was the age of capitalism. He had then escaped from the patron and had not yet been captured by the bureaucrat. . . . Yet it remains true that capitalism, which in many ways was kind to the artist and the intellectual generally, is doomed and is not worth saving anyway. So you arrive at these two antithetical facts: (1) Society cannot be arranged for the benefit of artists; (2) without artists civilisation perishes. I have not yet seen this dilemma solved (there must be a solution), and it is not often that it is honestly discussed.69

“There must be a solution”: Orwell offers none here, and one may wonder whether he ever found one. The best he seems to have been able to come up with, actually, was advocacy of a human “change of heart”—an argument of desperation.70 At least he honestly discussed the problem (as he saw it) of the potentially profound conflict between intellectual freedom and economic centralization. It is this dilemma, I think, which lies at the origin of Orwell’s “other” view of capitalism.

Arthur M. Eckstein is an author and a professor of history at the University of Maryland.

- The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, ed. Sonia Orwell and Ian Angus (New York, 1968), I, 5. ↩︎

- See T. R. Fyvel, George Orwell: A Personal Memoir (New York, 1982), p. 99. ↩︎

- CEJL, IV, 507. ↩︎

- CEJL, IV, 505. ↩︎

- See George Orwell, 1984: A Novel (New York, 1949), p. 5; p. 21 with pp. 118-119; p. 70; p. 76; p. 101; p. 120; pp. 121-122; p. 141. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 9 with p. 80; and p.81 with p. 121. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 92 and pp. 164-165. ↩︎

- 1984, p. 80, cf. pp. 9-11. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 129. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 169. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 77. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 168 ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 168. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 61-63; p. 83. ↩︎

- The evidence that this is a lie is collected just above. Interviews: 1984, pp. 74-78; artifacts: 1984, p. 9, cf. p. 80; p. 81; Goldstein’s Book: 1984, pp. 152-164. ↩︎

- See 1984, p. 157. ↩︎

- 1984, pp. 152-164 (Goldstein’s Book). ↩︎

- 1984, p. 146. ↩︎

- CEJL, IV, 502. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 120-121 (June? 1993). ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 330. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 525. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 525. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 525. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 525. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 526. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 526-527. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 525. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 527 (my italics). ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 409. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 409-410. ↩︎

- See the wry comment of Bernard Crick, George Orwell: A Life (London, 1980), p. 381. ↩︎

- CEJL, I, 538-539. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 96-103. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 96-109, especially 103 and 107. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 101-102. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 59 (my italics). ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 69-73; and 103. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 76. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 63. ↩︎

- Compare with 1984, p. 168. The same holds true with “Goldstein’s” claim about the spread of prosperity under capitalism: compare CEJL, 11, 76 (cited just above) with 1984, p. 168. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 49-50 (January 3, 1941). ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 401. ↩︎

- “Literature and Totalitarianism”: CEJL, 11, 134-137. “Will Freedom Die with Capitalism?” The Left News, April 1941, pp. 1682-1685 (not in CEJL and very difficult to get hold of in the United States). Neither of these pieces receives more than a bare mention in any scholarly study of Orwell; sometimes both are simply ignored, as in Crick’s monumental biography. ↩︎

- See Fyvel, pp. 123-124. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 134. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 135. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 135. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 135-136 (my italics). ↩︎

- See Norman Podhoretz, “If Orwell Were Alive Today,” Harper’s, January 1983, p. 37. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 137. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 137. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 502. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 502. ↩︎

- CEJL, IV, 246-247. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 325-326; III, 145; IV, 7; IV, 17; IV, 444; cf. already II, 73. ↩︎

- CEJL, II, 335; III, 118; III, 229-230; cf. III, 149. ↩︎

- Small businessmen: see CEJL, III, 208 also: IV, 25; IV, 176; IV, 465. “Capitalist democracy”: CEJL, II, 168; IV, 162; IV, 325. ↩︎

- See especially CEJL, 111, 117-118 (Orwell’s bitter remarks at the beginning of his tandem review of F. A. Hayek, The Road to Serfdom, and K. Zilliacus, The Mirror of the Past). Also: CEJL, II, 282; II, 429; 111, 12; IV, 410. ↩︎

- See CEJL, IV, 18; also: 111, 149. ↩︎

- See CEJL, IV, 309; IV, 323; IV, 392; IV. 398. ↩︎

- On the change of focus in Orwell’s social concerns, see Raymond Williams, George Orwell (New York, 1971), pp. 63-68. ↩︎

- Fyvel, p. 114. ↩︎

- Orwell as socialist: Fyvel, p. 114 and p. 208. The qualification: Fyvel, p. 208. ↩︎

- Fyvel, p. 208; Herbert Read, in his review of 1984, in George Orwell: The Critical Heritage, ed. Jeffrey Meyers (London/Boston, 1975), p. 285. ↩︎

- Alan Zwerdling, Orwell and the Left (New Haven/London, 1974), p. 109, part of Zwerdling’s excellent general discussion of Orwell’s pessimism, pp. 96-113. ↩︎

- George Woodcock, “George Orwell, 19th Century Liberal,” in Meyers, p. 246; Bertrand Russell’s obituary of Orwell, in Meyers, p. 300. ↩︎

- See especially CEJL, IV, 159. ↩︎

- CEJL, III, 229-230 (my italics). ↩︎

- See CEJL, IV, 18; also: II, 15-18. ↩︎