“Individualism” is a problematic term in American conservative thought. The cause goes back to the fundamental tension in American conservatism between its libertarian and traditionalist strains. Exponents of the former strain, which often seems to echo and amplify the liberalism of nineteenth-century Europe, are likely to regard individualism in favorable terms, as an affirmation of the human person, and as a counter to the oppressive statism, collectivism, and conformism of socialist and nationalist thought. Exponents of the latter strain, however, see individualism as one of the chief pathologies of modernity, another element in the abstract, rationalistic, nakedly self-interested, egalitarian, leveling, atomistic, antitraditional, and antinomian tendencies that have disordered the present age. At its best, however, American conservatism has sought to navigate between these extremes and has found a variety of ways to reconcile liberty and order and to view them as complementary rather than contradictory.

Hence, “individualism” is not invariably a negative term in American conservative discourse. One often sees the term used favorably in what might be called the Hoover–Taft–Goldwater line of antistatist political discourse, often with the adjective “rugged” attached to it. But even traditionalist conservatives are likely to speak well of individualism from time to time, and not only when they are attacking totalitarianism or the welfare state. This should not be surprising, for conservatism places a high value upon the individual, even if it also at the same time tends to question the concept of individual autonomy. Consider the fact that the Intercollegiate Studies Institute, one of the main bastions of traditionalist conservative thought in America, began life as the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists. Or that Richard M. Weaver, a hero of traditionalist conservatives, extolled what he labeled “social-bond individualism” as an alternative to both collectivism and atomism. Yet the very awkwardness of Weaver’s paradoxical term bespeaks both the necessity of reconciling the two divergent strains and the difficulty entailed in actually doing so.

Some longer historical perspective on the subject, however, should help us to clarify the matter. For, although “individualism” is a relatively new term in Western intellectual and religious history, it has a long and distinguished pedigree, informed by rich antecedents and fertile anticipations. Belief in the dignity and worth of the individual person has always been a distinguishing mark, and a principal mainstay, of what we call Western civilization, the defense of which has become an increasingly central element in what now goes by the name of conservatism.

Elements of that belief can be detected as far back as classical antiquity, particularly in the Greek discovery of philosophy as a distinctive form of free rational inquiry, and in the Greco-Roman stress upon the need for virtuous individual citizens to sustain a healthy republican political order. Other elements appeared later, particularly in the intensely self-directed moral discipline of Epicureanism and Stoicism. Even more importantly, the traditions and institutions arising out of biblical monotheism, whether Jewish or Christian, placed heavy emphasis upon the infinite value, personal agency, and moral accountability of the individual person. That emphasis reached a pinnacle of sorts in Western Christianity, which incorporated the divergent legacies of Athens and Jerusalem into a single universalized faith.

None of these expressions of belief in the individual were quite the same as modern individualism, however, for the freedom the premodern individual enjoyed, particularly since the advent of Christianity, was always constrained. It was constrained by belief in the existence of an objective moral order not to be violated with impunity by antinomian rebels and enthusiasts. And it was constrained by belief in the inherent frailty of human nature, which indicated that virtue cannot be produced in social isolation. Although almost all influential Western thinkers before the dawn of modernity had conceded the importance of the individual, none used the term “individualism” to express that belief.

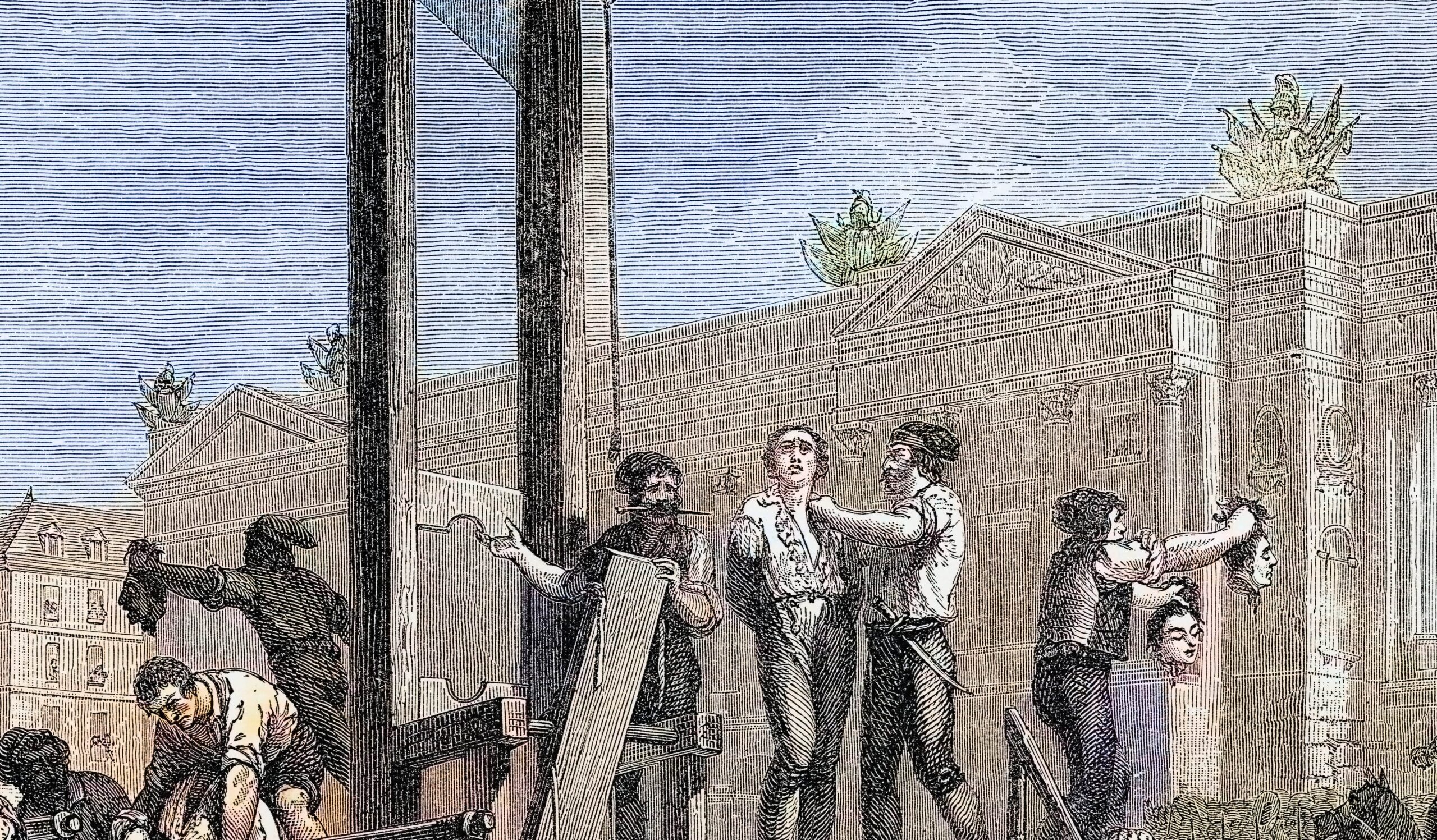

Instead, “individualism” first arose in the discourse of opposition to the French Revolution. The nineteenth-century French writer Joseph de Maistre used the word to describe what he found horrifying about the revolution: its overturning of established social hierarchies and dissolution of traditional social bonds in favor of an atomizing doctrine of individual natural rights that freed each individual to be his or her own moral arbiter. For Maistre, individualism was not an affirmation of dignity, but a nightmare of moral anarchy, a nightmare that he rendered in startlingly vivid terms.

The French writer Alexis de Tocqueville, in his classic study Democracy in America (1835), had a more subtle and enduring analysis. He believed individualism to be America’s self-conscious social philosophy, a view of the social world fostered by the rise of democracy that “disposes each member of the community to sever himself from the mass of his fellow-creatures: and to draw apart with his family and friends: so that . . . he willingly leaves society at large to itself.” For Tocqueville, individualism was something new under the sun, a conscious and calculated withdrawal from the responsibilities of citizenship and public life. For Tocqueville—who was, unlike Maistre, a qualified friend of democracy—there was no greater threat to the new order than this tendency toward privatism.

Even Tocqueville’s more moderate view seems strikingly at odds with the self-conception of most Americans, who after all had little experience of feudal, aristocratic, monarchical, and other premodern political institutions, and who are likely to see individualism, in one form or another, as a wholly positive thing, the key ingredient in what it means to be American. Such a view is, of course, a bit too simple. It presumes that American history is nothing more than the story of an unfolding liberal tradition, a tale that can be encapsulated in the classic expression of individual natural rights embodied in the Declaration of Independence. Such a view ignores the profound influence of religious, republican, radical communitarian, socialist, and other nonliberal elements in our national saga, including the most illiberal institution of all, slavery. What national commitment to individualistic values we now possess has certainly evolved over time, and there have always been countercurrents challenging the mainstream.

Nor, for that matter, is it always easy to know what is meant by the term “individualism.” It is used, albeit legitimately, in a bewildering variety of ways. It may refer to the self-interested disposition of mind that Tocqueville described or to the passionate egotism Maistre deplored or to the self-reliant frontiersman or self-made small businessman praised in American popular lore. Individualism may be taken to refer to an understanding of the proper relationship between the individual and society or state, wherein the liberty and dignity of the former is to be protected against the aggrandizing or social-conformist pressures of the latter. More radically, it may point toward a philosophy of the state or society in which all political and social groups are viewed as mere aggregations of otherwise self-sufficient individuals, whose social bonds are entirely governed by consensual contract. Even more radically, it may point toward the increasingly popular view that, to the maximum degree possible, the individual should be regarded as an entirely morally autonomous creature—accountable to no person and no putative higher law, armed with inviolable rights, protected by a zone of inviolable privacy, and left free to grow and develop as the promptings of the self dictate. All these meanings of individualism have in common a presumption of the inherent worth of the individual person, but they may diverge in dramatic ways.

And yet, disclaimers aside, there can be little doubt that the dominant American tradition in our own day has become one of endorsing the highest possible degree of individual liberty and self-development in political, religious, social, and economic affairs. The pejorative connotation that individualism had at the time of its origins never took deep hold in Anglo-American discourse. If anything, the language of individual rights, and the tendency to regard individual men and women as self-contained, contract-making, utility-maximizing, and values-creating actors, who accept only those duties and obligations they elect to accept, has grown steadily more powerful and pervasive in the early part of the twenty-first century. The recourse to individual rights, whether expressed as legal rights, voting rights, expressive rights, reproductive rights, sexual rights, membership rights, or consumer rights, has become the near-invincible trump card in most debates regarding public policy, and it is only in the rarest instances (such as the provision of preferential treatment for members of groups that have been subjected to past legal or social discrimination) that this trump has been effectively challenged. The fundamental commitment to what Elizabeth Cady Stanton called the “solitary self” has never been stronger.

Conservatives are hard put to mount an effective challenge to this hegemony of rights talk. For one thing, they have to rely on rights talk themselves, as a way of defending their own right to be heard. The loudest and most convincing complaints about political correctness, speech codes, and ideological orthodoxy in the academy now come from conservatives, who might otherwise be silenced entirely. Then, too, there is the fact that so many American conservatives are libertarians, particularly in economic matters and increasingly so in matters of personal morality and social policy as well. Such libertarian commitments often take precedence over questions of social cohesion or the public good, including matters such as land use and environmental or economic policy, or the soundness of the social fabric, matters that used to be at the heart of conservative thought.

More fundamental, though, is the question of how much strength remains in the primary institutions of family, marriage, church, and local community upon which traditionalist conservatism was built and by which the American penchant for individualism has been restrained in the past. Such fragile institutions, and the habits of reverence, accountability, and rootedness they engender, will have little binding power in a utility-maximizing world, where radical individualism is allowed to run riot. As a consequence, much of the gloomy mood of conservative social theory in the past fifty years has taken its cue from Robert Nisbet’s classic 1953 work, The Quest for Community, seeing the decay of such primary institutions and other “intermediate associations” as profound and irreversible.

Yet Nisbet himself offered grounds to think this view might be too gloomy. As he made clear, there is an enduring point of common ground between the libertarian and traditional critiques of modern America—and that is the aversion both share to the overwhelming dominance of the modern centralized nation-state. As Tocqueville well understood, individualism is itself the product of a particular form of socialization. Radical centralization and radical individualism go hand in hand, precisely because centralization gradually eliminates the functional need for individuals to understand and comport themselves as social creatures, accountable to one another and nourished by and embedded in their proximate social contexts. If, on the other hand, the trend toward centralization could be reversed and social policy be consciously reoriented toward the preservation and strengthening of intermediate associations, it seems reasonable to suppose that the current excesses of individualism might also begin to recede and the tension between individual liberty and social order might be made less intense, and more fruitful, than it is at present. Whether that is possible remains to be seen, of course. But it is not unthinkable.

Further Reading

Wilfred M. McClay, The Masterless: Self and Society in Modern America

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 427.