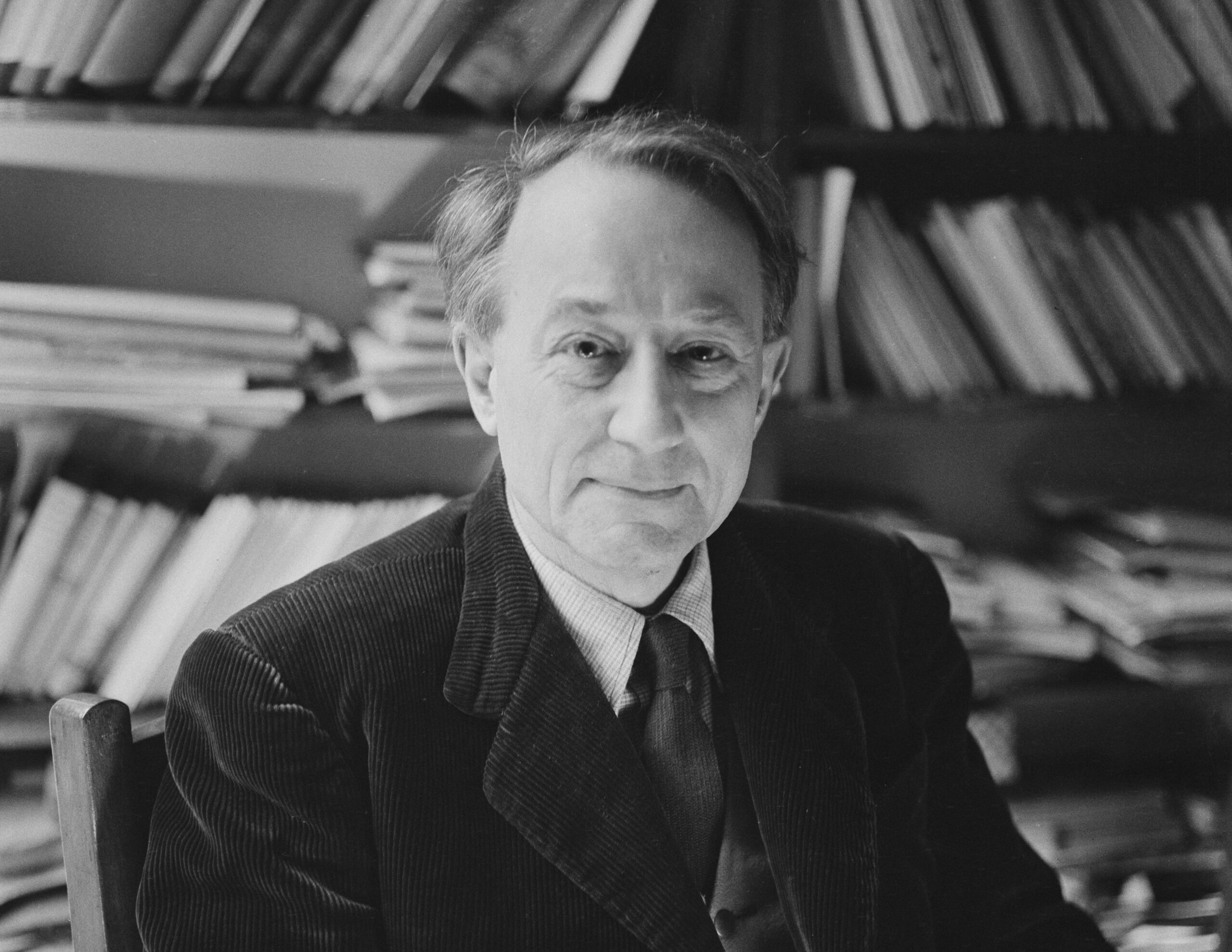

Michael Oakeshott was among the most notable political philosophers of the twentieth century and a distinguished exponent of the “conservative disposition.” Among his important contributions are his interpretation of the thought of Thomas Hobbes, critique of modern rationalism, magisterial essay on “The Rule of Law,” theory of civil association and political authority, philosophy of history, and philosophy of education. Oakeshott read modern history at Cambridge University and then taught there from 1926 until 1948. After a brief period at Oxford he was appointed, in 1951, as the professor of political science in the government department at the London School of Economics, a post he held until retiring in 1968.

His most important books are Experience and Its Modes (1933), Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays (1962), and On Human Conduct (1975). The most accessible introduction to Oakeshott’s thinking is the collection of essays in Rationalism in Politics. There one finds the pieces titled “On Being Conservative,” “The Political Economy of Freedom,” “Political Education,” and “The Tower of Babel.” These, together with the posthumously published The Politics of Faith and the Politics of Scepticism (1996), constitute a clear statement of his conservative disposition.

Oakeshott described himself as a “skeptic.” He meant, following St. Augustine and Montaigne, skepticism about human pretensions to succeed in “the pursuit of perfection as the crow flies,” to build towers into a putative heavenly kingdom, or to control and manage the contingencies of human existence. Such aspirations he admired in individuals, for he applauded individuals seeking their fortunes as they defined them for themselves, but he deplored such aspirations in governments. He did so because he saw the state as a basically involuntary but necessary arrangement presiding over diverse people and interests. To invest in a single ideal would necessarily impose on some for the sake of others, suppressing the natural diversity which is the ground of human freedom. What is preferable is a “civil association” in which diverse people with diverse interests acknowledge and subscribe to a rule of law to insure the basic order they must have, with a view to affording the greatest freedom to live according to their own self-understandings. Oakeshott thought that this was the principal achievement of modern Europe, first emergent in the fifteenth century, gaining grand theoretical expression in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and persisting against fierce attacks in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The achievement may be described as the transformation of relations of command and obedience into relations of authority and acknowledgment, and it was possible because the ideal of the self-regulating individual, competent to pursue individual interests within mutually acknowledged procedural restraints, and not dependent on coercive enforcement, was increasingly instantiated in practice in modern European history.

Nevertheless, as the technical and military power of modern governments began significantly to increase, they brought with them the temptation to invest modern governments with grand purposes for the redesign or reconstruction of social orders. This practical turn of events was encouraged theoretically by the influential growth of “rationalism” in modern Europe under the influence of the thought of Francis Bacon and Descartes and later of Jeremy Bentham and the modern social sciences. Rationalism, as Oakeshott described it, proposes techniques or methods of analytic reasoning, inspired by the natural and mathematical sciences, by means of which we may overcome the contingent character of historical existence. In extreme form, it holds that the hitherto endless activity of preserving and changing in politics can be brought to a satisfactory conclusion, and that this is to be done by a coalition of the intellectually enlightened with governments, a coalition that will direct the use of power in steering people to the right end.

The result is that modern politics is conducted in a charged field polarized between a skeptical attitude towards governmental power and the view that such power is the means to infinite improvement. The contest between the skeptic and the rationalist has proven historically irresolvable, although Oakeshott thought that in recent times rationalism had clearly—and, he thought, regrettably—dominated over political skepticism. But because of the power in practice of the ideas of civil association, of rule of law, of authority grounded in acknowledgment rather than in coercion, and because he thought these to be more consistent with the human spirit, Oakeshott believed that this remarkable modern achievement would maintain itself. Modern politics is thus constituted in the tension between competing traditions of thought. They play off of each other and the character of each is shaped by the presence of the other. Regardless of his personal preferences in the matter, he thought that this was the reality of our situation.

For Oakeshott, the main task of modern governments was, then, to “keep the ship afloat” so that individuals and voluntary associations could seek their fortunes and define for themselves their destinations within a procedural system of laws. This must be done within the context of dispersed power wherein the state, while not especially strong, and with few resources to distribute, was strong enough to resist informal conglomerations of power that would turn the civil association into a managerial enterprise, a modern form of the Tower of Babel. Here then is the “conservative disposition.” It is not the same as a philosophical understanding. For Oakeshott, philosophy is seeking in detachment simply to understand, and to describe, what is going on in the world. Rather, conservatism is a considered practical response to the opportunities and perils of modern political life. What Oakeshott offered was a picture of the philosophical and historical context within which to identify more clearly what prompts the conservative disposition. He did not think philosophy could resolve the issues but could only clarify them in ways their practitioners would likely not consider. In expressing his preference for one pole, however, he associated himself with an ancient tradition in the West which denies to politics the highest honor. He called politics a “necessary evil,” meaning thereby to say both that we cannot do without politics and that from its necessity does not follow its candidacy to be the source of all meaning.

Further Reading

Robert Devigne, Recasting Conservatism: Oakeshott, Strauss, and the Response to Postmodernism

Michael Oakeshott, Hobbes on Civil Association

Michael Oakeshott, Religion, Politics, and the Moral Life

This entry was originally published in American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia, p. 641.